This is the

first part of a blog series involving the Real

Madrid State aid case.

Apart from being

favoured by many of

Spain’s most important politicians, there have always been suspicions

surrounding the world’s richest football club regarding possible financial aid by the Madrid City Council. Indeed, in

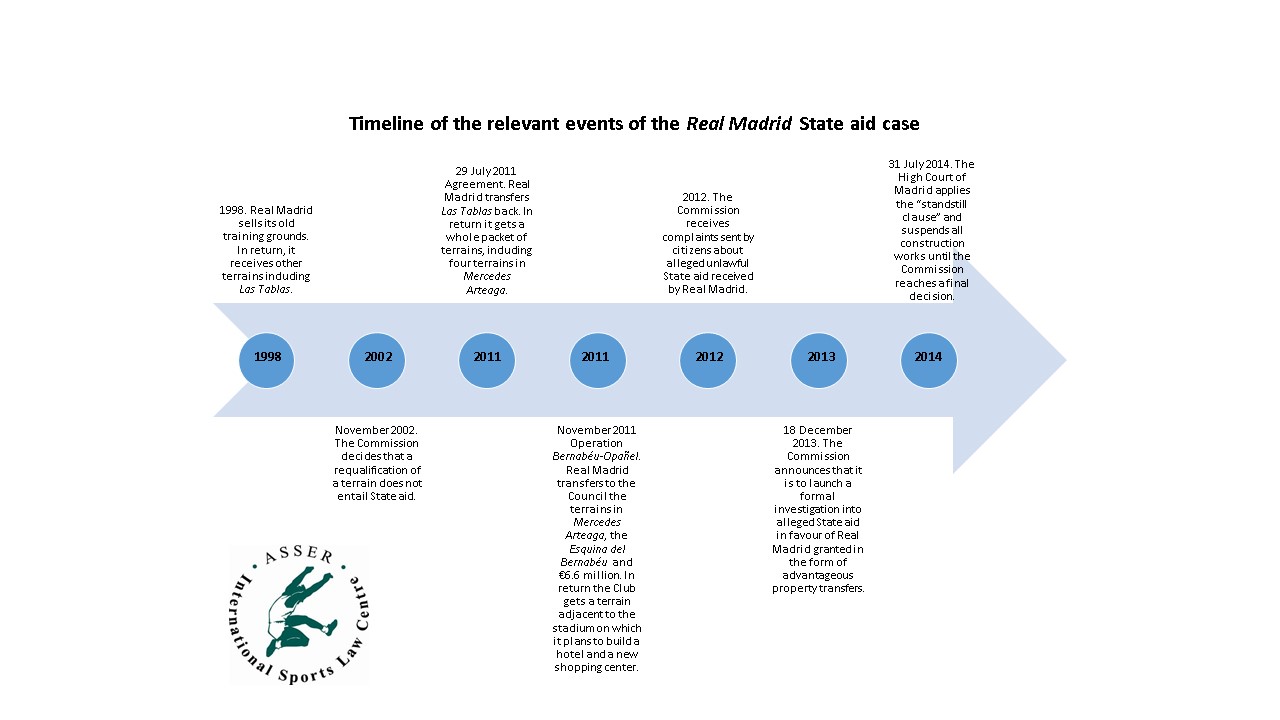

the late 90’s a terrain qualification change by the Madrid City Council proved to

be tremendously favourable to the king’s club. The change allowed Real Madrid

to sell its old training grounds for a huge sum. Though the exact price for the

grounds remains unknown, Real Madrid was suddenly capable of buying players

like Figo and Zidane for record fees. However, the European Commission, even

though agreeing that an advantage was conferred to the club, simply stated that the new

qualification of the terrain in question does not appear to involve any

transfer of resources by the State and could therefore not be regarded as State

aid within the meaning of article 107 TFEU.

Agreements

between the club and the Council have been a regularity for the last 25

years. A more recent example concerns an

agreement signed on 29 July 2011 (Convenio29-07-2011.pdf (8MB).

The agreement regularizes two earlier agreements between the Council and Real

Madrid dating from 1991 and 1998 respectively. The commitments deriving from

those earlier agreements were not followed by the relevant parties and

therefore had to give way to a new agreement. A closer look at the 29 July 2011

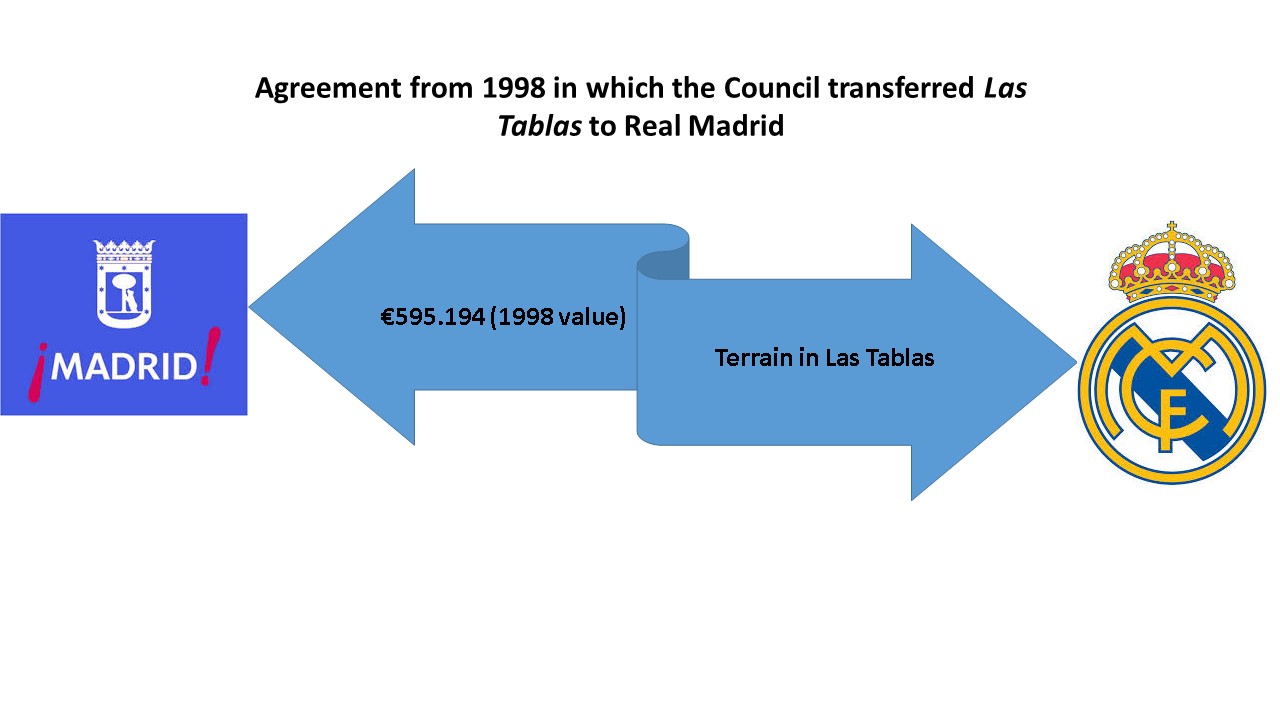

Agreement exposes a bizarre chain of events. It turned out that in 1998 Real

Madrid transmitted an undivided half of their old training grounds to the

municipality. Apart from a large sum of money, the club was to receive a number

of terrains spread out over the municipality, including a terrain located in

the area called Las Tablas valued at

€595.194 in 1998. However, due to its qualification for sporting usage, the

Council concluded in 2011 that the parcel could not be transferred to the club

due to the fact that Madrid’s urbanity laws only permit a transfer of urban or

urbanizable terrains. For that reason, the Council agreed to compensate the

football club not for the original value of €595.194 but for a staggering €22.693.054,44! Real Madrid was not compensated in the form

of a sum, but rather it was presented with a packet of terrains including four

terrains of a total area of 12.435 m/2 in the street Mercedes Arteaga in the Carabanchel district of Madrid.

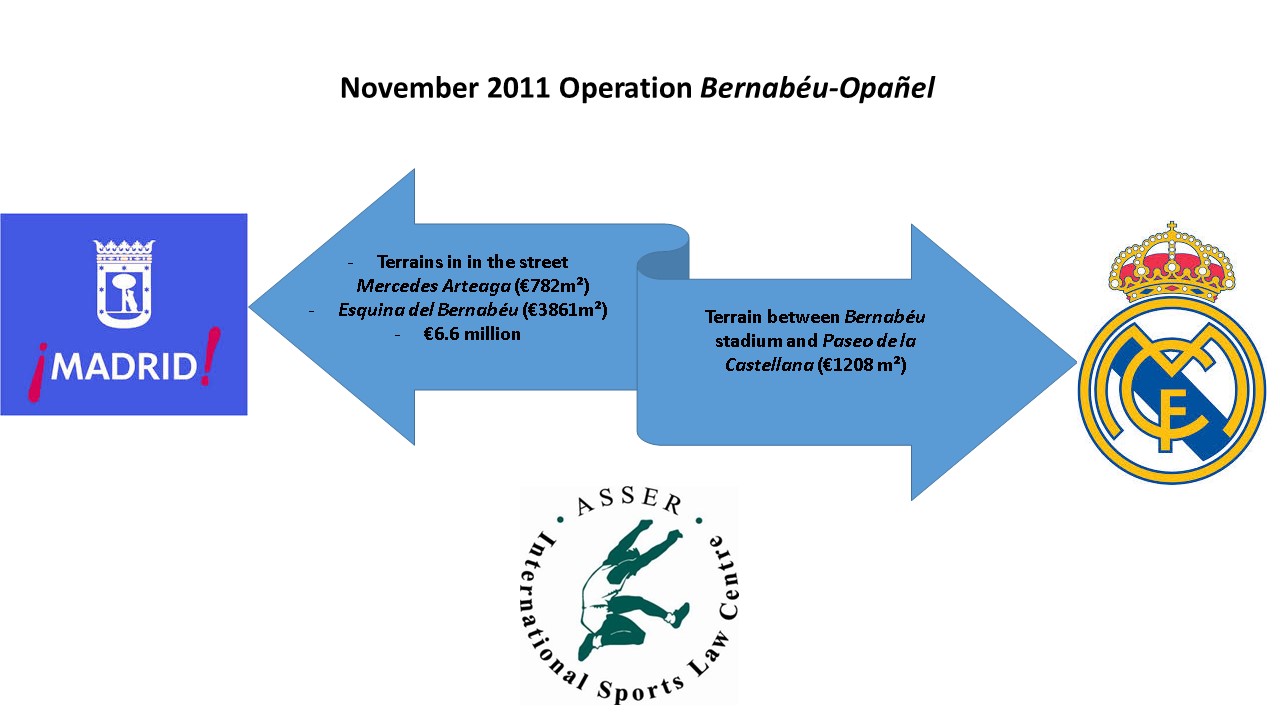

The year 2011 also saw a second agreement between the Council of Madrid

and the football club, this time concerning construction works on the Real

Madrid stadium Santiago Bernabéu.

This agreement, dating from November 2011, is known as operation Bernabeú-Opañel and includes the following plans. The Council is to transfer to the club a terrain constituting a 12.250

m/2 buildable surface which borders the west-side of the Bernabéu stadium. This acquirement permits Real Madrid to cover the

stadium with a roof, to build a shopping centre and a hotel on the façade

situated on the Paseo de la Castellana

(one of Madrid’s most important streets). In return, the club firstly agreed to

transfer to the Council the shopping centre Esquina

del Bernabéu, which is situated at the South-East-side of the stadium with

a buildable surface of 6.858 m/2. The Council would then demolish the shopping

centre and convert it into a public park. Secondly, the club is to transfer

back to the Council part of the four terrains located in the street Mercedes Arteaga that it received as

part of the 29 July 2011 Agreement. In

addition to the transfers of the old shopping centre and the terrains located

in the street Mercedes Arteaga, Real

Madrid is also to pay €6.6 million to the Council. The Council, however,

encountered an obstacle in its own urban laws. The Plan General de Ordenación Urbana de Madrid de 1997 (PGOU) did not

permit private parties, like Real Madrid, to construct on public terrains owned

by the Council. Therefore, on 16 November 2012, the Government of the

autonomous region of Madrid announced that the PGOU is to be modified ad hoc for the

operation Bernabeú-Opañel.

By means of the operation Bernabeú-Opañel,

Real Madrid expressed that it hopes to “convert the Club in a sporting institution of reference

in the world. The aim is for the stadium to have a maximum level of comfort and

services superior to the most modern and advanced sporting stadiums in the

world” (PropuestaRealMadrid.pdf (914.2KB)). According to the Council, the operation will not only improve sporting

and leisure facilities in the city, it will also create up to 9.546 m/2 of

“green zones”. Moreover, the investment for the construction works will be

borne only by Real Madrid and it is expected that the construction works will

give employment to more than 2 000 people and the exploitation to 600 people.

In 2012, the ecological movement Ecologistas

en Acción found several legal irregularities with regard to the 29 July Agreement operation

Bernabeú-Opañel and (unsurprisingly)

concluded that the agreements appeared to be very beneficial for Real Madrid. It

therefore started legal proceedings in front of the Spanish administrative

Court claiming that the ad hoc modification of the PGOU was illegal. It would later on launch on appeal in front of the Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Madrid, or Madrid High Court (TSJM-Order-31-07-2014.pdf (112.3KB)). Simultaneously, it informed the European Commission of potential

unlawful State aid granted by the Council of Madrid to Real Madrid. To Spain’s outrage, on 18 December 2013, the Commission declared

that it had enough reasons to believe that the incriminated transactions might

involve State aid and launched a formal investigation in accordance with Article 108(2) TFEU. Concretely,

the Commission expressed the following concerns:

In 2012, the ecological movement Ecologistas

en Acción found several legal irregularities with regard to the 29 July Agreement operation

Bernabeú-Opañel and (unsurprisingly)

concluded that the agreements appeared to be very beneficial for Real Madrid. It

therefore started legal proceedings in front of the Spanish administrative

Court claiming that the ad hoc modification of the PGOU was illegal. It would later on launch on appeal in front of the Tribunal Superior de Justicia de Madrid, or Madrid High Court (TSJM-Order-31-07-2014.pdf (112.3KB)). Simultaneously, it informed the European Commission of potential

unlawful State aid granted by the Council of Madrid to Real Madrid. To Spain’s outrage, on 18 December 2013, the Commission declared

that it had enough reasons to believe that the incriminated transactions might

involve State aid and launched a formal investigation in accordance with Article 108(2) TFEU. Concretely,

the Commission expressed the following concerns:

1) The Commission doubts whether it

was impossible for the Council of Madrid to transfer the Las Tablas property to Real Madrid;

2) The Commission doubts that a

market value of the Las Tablas plot

of land has been sought;

3) The Commission doubts the market

conformity of the value of the properties which were transferred to Real Madrid

by the 2011 Agreement and at the occasion of the subsequent further exchange of

land around the Bernabéu Stadium, and;

4) The Commission doubts that there

is an objective of common interest, which could justify selective support to a

very strong actor in a highly competitive economic sector.

The Commission’s doubts seem, in light of the

facts at hand, reasonable. To decide whether or not the land transactions qualifies

as unlawful State aid, however, the four cumulative criteria of Article 107(1)

TFEU need to be fulfilled. (1) The aid must confer an economic advantage on Real

Madrid; (2) it must be granted by a Member State or through State resources;

(3) the advantage must be selective and distorts or threatens to distort competition;

and (4) it must affect trade between Member States.

Advantage to Real

Madrid over its competitors

As the Commission pointed out in paragraph 21 of its notice initiating

the infringement procedure against Spain, “Real Madrid appears to enjoy an

economic advantage from the fact that a plot of land, which at the time of its

acquisition was valued at €595,194, appears 13 years later, in an operation to

offset mutual debts, with a value of more than €22 million”. Furthermore, there

are also doubts regarding the market conformity of the lands transferred in the

operation Bernabéu-Opañel. In

situations where the public authorities wish to sell public property to private

investors, it should make sure that the revenue obtained from the sale is

comparable to market level. This criterion is also known as the “market economy

vendor principle”. In accordance with the Land sale Communication, should the public

authorities wish to avoid any advantage to the recipient over its competitors

during a land sale transaction, it should apply one of the two following

procedures: (1) an unconditional bidding procedure or (2) a procedure where the

land is valued by one or more independent asset valuers prior to the sale

negotiations. The Court of Justice has ruled that other methods may also

achieve the same result, but in order to comply with EU State aid rules, the

national provisions establishing rules for calculating the market value of land

must in all cases lead to a price as close as possible to the market value.[2] Special obligations for

the buyer, such as urban planning requirements, do play a role when determining

whether or not the land was sold at market value. Furthermore, land transfer deals,

which often consist of more than just one land transaction, have to be

scrutinized in their entirety.[3]

Therefore, to determine whether an advantage was conferred to Real Madrid, both

agreements between the club and the Council have to be take into account with a

special focus on the valuation methods used.

In 1998, the valuation for the terrain in Las Tablas (€595,194) was done by the administration of Madrid, on

the basis of legislation which offers a technique to determine the value of

urban real property. The calculated value for the same terrain in Las Tablas in 2011 amounted to €22.693.054,44. According to a valuation report released by the

Municipal Valuation Department, the

value was calculated in accordance the same application rules. Yet it has to be

borne in mind that the Municipal Valuation Department forms part of the Área de Gobierno de Urbanismo y Vivienda del

Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Not only is the Área

de Gobierno de Urbanismo y Vivienda the main public authority regarding

urban planning in Madrid, it is together with Real Madrid the main party in the

2011 Agreement itself.

Real Madrid was not compensated in the form of a payment, but rather it

was presented with another packet of terrains valued at €19,972,348.96. In the

valuation report released by the Municipal Valuation Department, a list is included with average terrain

values per district calculated by the independent appraiser Tasamadrid. In continuation, the

Municipal Valuation Department applied a formula based on its own legislation

to determine the final value of the terrains. This packet of terrains included

land in the street Mercedes Arteaga,

valued at €4,360,862 which were transferred back to the municipality in the

operation Bernabéu-Opañel.

The operation Bernabéu-Opañel

also included the club transferring the old shopping centre Esquina del Bernabéu and added a payment

of €6,6 million. A second valuation report indicates that the value of the Esquina del Bernabéu is €3,861 per

square meters passed on the average values of terrains found in adjacent

streets. Furthermore, the Council “requalified” the terrain between the Bernabéu stadium and the street Paseo de la Castellana by ad hoc

modifying the local urban laws (PGOU) before transferring it to Real Madrid. The

value of this terrain is also calculated in the second report and ads up to

€1,208 per square meter. Even though two of the terrains in question can be

found in the same area, the value per square meter of the Esquina Bernabéu is much higher (€3,861) as compared to the value

of the land between the Bernabéu stadium

and the street Paseo de la Castellana

(€1,208). True, the terrain with the Esquina

del Bernabéu has already been built on, thereby increasing the value, but

one should keep in mind that the operation Bernabéu-Opañel

consists of demolishing the Esquina del

Bernabéu and turning it into a green zone. On the other, the other terrain

will be used for the construction of a hotel and a new shopping centre.

Secondly, a quick glance at other real estate transfers in the same area of

Madrid shows that the value of the terrains is in fact much higher. In 2012,

the Picasso tower was purchased by a private firm for €400 million, or €5000

m/2. Today, the building Torre Titania

can be bought for €11,000 m/2 and the building Castellana 200 is for sale for €150

million.

With all the above in mind, one could legitimately get the feeling that

the actual aim of the Agreement of 29 July 2011 was to pave the way for the

operation “Bernabéu-Opañel”, as some media suggested. Unlike in the Konsum Nord case, where the General Court held that the presence of

a link between different transactions could mean that the measure in question does

not constitute State aid, the link between the agreements in the Real Madrid

case only increases suspicions regarding unlawful State aid. Furthermore, the

Council of Madrid has also been inconstant regarding its valuation methods. The

value of the terrain in Las Tablas

was calculated without an independent appraiser and the value of the Esquina del Bernabéu was calculated using

the average value of terrains found in adjacent streets. In short, there are

good reasons to believe that the transactions were made in order to provide a

financial advantage to Real Madrid.

The remaining three criteria of Article 107(1) TFEU and possible

justifications will be discussed in an upcoming blog post.

[1] Notes are omitted. A comprehensive article can be accessed at Oskar van Maren, "The Real Madrid case: A State aid case (un)like any other?".

[2] Case C-239/09 Seydaland

Vereinigte Agrarbetriebe [2010] ECR I-13083, §33-35

[3] Case T-244/08 Konsum Nord ekonomisk förening v Commission [2011] ECR II-0000, §58