Editor’s note: You will find attached to this blog the background paper to the event Five Years Later: Rana Plaza and the Pursuit of a Responsible Garment Supply Chain hosted by the Asser Institute in The Hague on 12 April.

Background paper: executive summary

Raam Dutia & Abdurrahman Erol (Asser Institute)

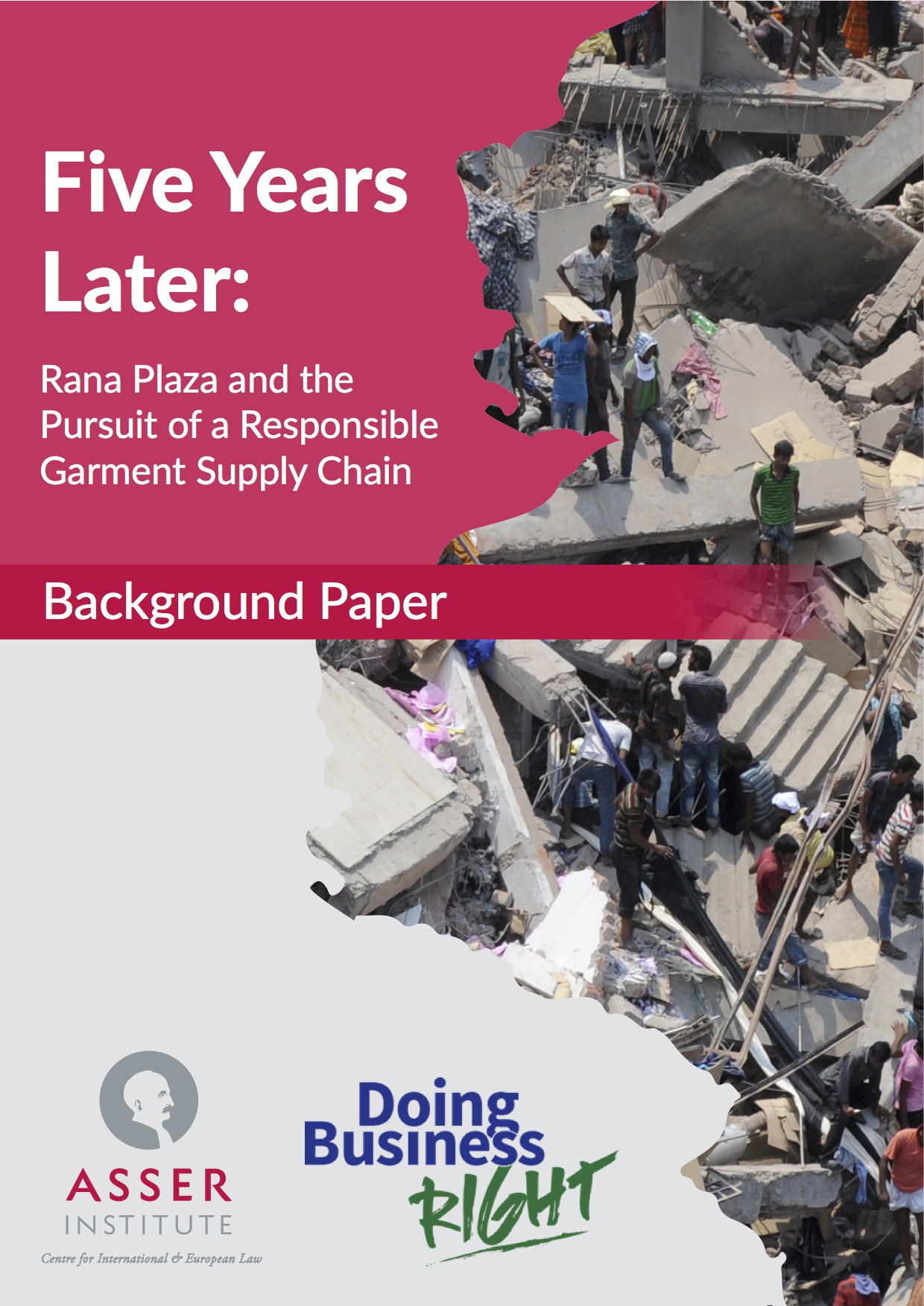

The collapse of the Rana Plaza building on 24 April 2013 in Savar, Bangladesh, left at least 1,134 people dead and over 2,500 others wounded, while survivors and the families of the dead continue to suffer trauma in the aftermath of the disaster. The tragedy triggered a wave of compassion and widespread feelings of guilt throughout the world as consumers, policy makers and some of the most well-known companies in Europe and North America were confronted with the mistreatment and abject danger that distant workers face in service of a cheaper wardrobe.

Partly in order to assuage this guilt, a number of public and private regulatory initiatives and legal responses have been instituted at the national, international and transnational levels. These legal and regulatory responses have variously aimed to provide compensation and redress to victims as well as to improve the working conditions of garment workers in Bangladesh. Mapping and reviewing how these responses operate in practice is essential to assessing whether they have been successful in remedying (at least partially) the shortcomings that led to the deaths of so many and the injury and loss suffered by scores more.

This briefing paper outlines and provides some critical reflections on the steps taken to provide redress and remedy for the harm suffered by the victims of the catastrophe and on the regulatory mechanisms introduced to prevent its recurrence. It broadly traces the structure of the panels of the event.

In line with Panel 1 (Seeking Justice, Locating Responsibility), the paper begins by focusing on litigation that has been conducted to secure justice and compensation for the victims, as well as to bring the relevant actors to account for their alleged culpability for the collapse. To this end, the paper examines the avenues that have been taken to hold corporations legally accountable in their home jurisdictions for their putative contributions to the collapse on the one hand, and individuals (particularly local actors) legally accountable before the courts in Bangladesh on the other; it then considers softer mechanisms aimed at compensating victims and their dependants.

In keeping with Panel 2 (Never again! Multi-level regulation of the garment supply chain after Rana Plaza: Transnational Responses), the paper then considers the transnational (public and private) regulatory responses following the tragedy, enacted by stakeholders including NGOs, industry associations, trade unions and governments and largely connected to issues surrounding labour standards and health and safety.

Finally, in line with Panel 3 (Never again! Multi-level regulation of the garment supply chain after Rana Plaza: National Responses), the paper looks at numerous (soft and hard) regulatory developments at the national level in response to the Rana Plaza collapse. It charts the legislative response by the government of Bangladesh to attempt to shore up safety, working conditions and labour rights in garment factories. It also focuses on legislative and other arrangements instituted by certain national governments in the EU, and how these arrangements relate to the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises.

Download the full paper: RanaPlazaBackgroundPaper.pdf (3.5MB)