On 24 and 25 October 2024, the Asser Institute in The Hague will host the 2024 edition of the International Sports Law Journal (ISLJ) Conference. The ISLJ is the leading academic journal in transnational sports law and governance and is proud to provide a platform for transnational debates on the state of the field. The conference will address a number of issues of interest to the ISLJ and its readers.

Register HERE

Drivers and effects of reform in transnational sports governance

Transnational sports governance seems to be in a permanently unstable state of crisis and reform. At regular interval, international sports governing bodies face scandals triggered by corruption investigations or human rights violations, as well as adverse judidicial decisions. These are often followed by waves of institutional reforms, such as the creation of new bodies (E.g. the Athletics Integrity Unit), the adoption of new codes and regulation (such as Codes of Ethics) or human rights commitments (e.g. FIFA and the IOC’s Human Rights Policy/Strategy). This dynamic of crisis and reform will be at the heart of this year’s ISLJ conference, as a number of panels will critically investigate the triggers, transformative effects and limited impacts of reforms in transnational sports governance.

Football in the midst of international law and relations

As the war in Gaza and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continue to rage, it has become even clearer that the football world can hardly be entirely abstracted from international relations. Yet, FIFA and UEFA continue to insist on their neutrality and to deny that their governance is (or should be) affected by the world’s political affairs. During the conference, we will engage with case studies in which football is entangled with international politics and law. In particular, the speakers will delve into the role of FIFA and UEFA in such situations and on the legal standards and processes that should be applied throughout their decision-making.

Olympic challenges of today and tomorrow

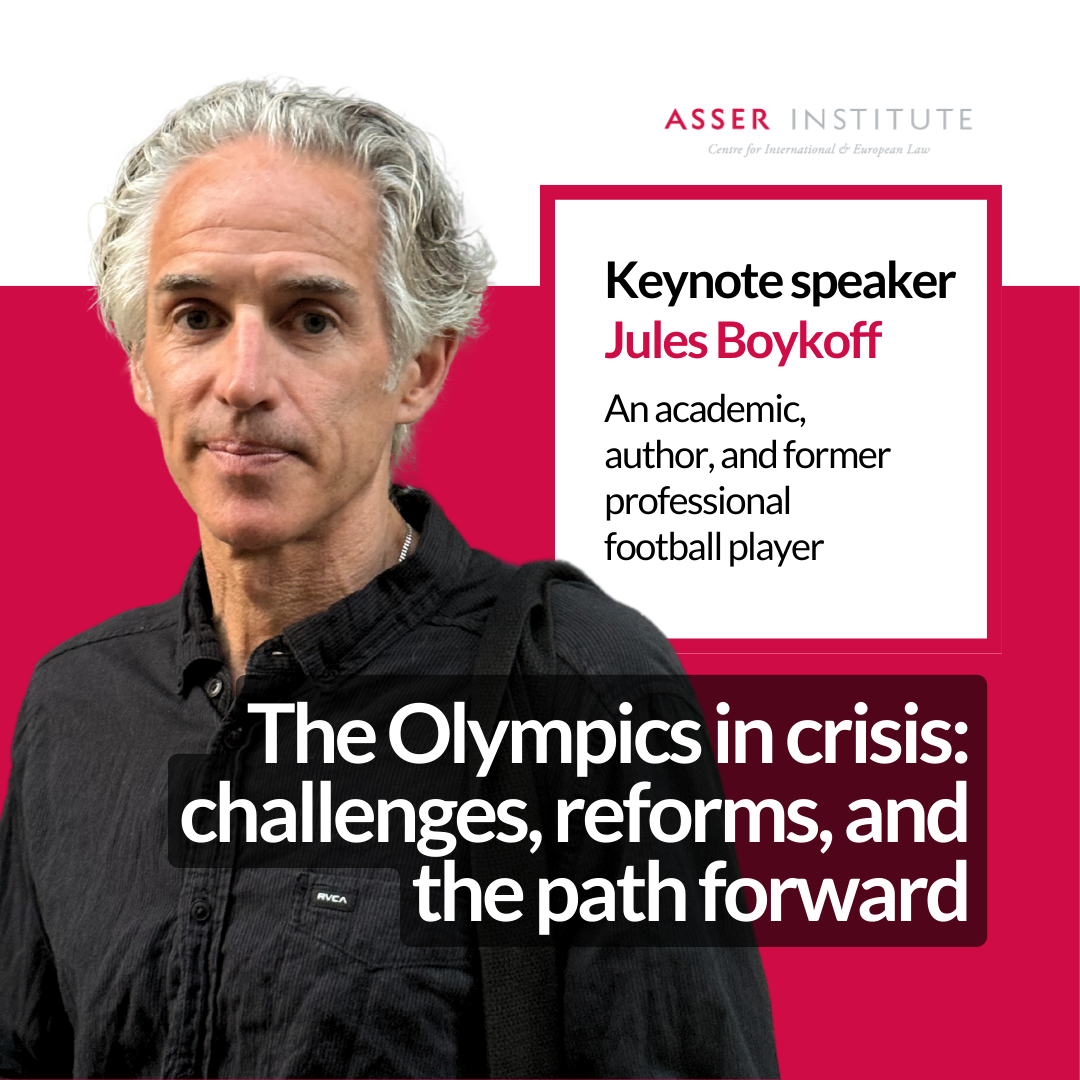

While the Paris 2024 Olympics have come to a close, the legal questions they have raised are far from exhausted. Instead, the Olympics have highlighted new issues (such as the question of the legality of the hijab ban imposed by the French Federation on its athletes) or old ones (such as the question whether Olympians should be remunerated by the IOC or the international federations), which will be discussed by our speakers. Finally, with the help of our keynote speaker, Prof. Jules Boykoff, a longstanding critique of the current Olympic regime, we will explore the IOC’s capacity to adapt to challenges while resisting radical change to the current model of olympism.

Download the full programme

Online participation available

Following the success of our webinar option in the past years, we are once again allowing online participation to the conference at an affordable price. Thus, we hope to internationalise and diversify our audience and to reach people who are not in a position to travel to The Hague.

We look forward to welcoming you in person in The Hague or digitally to this new iteration of the ISLJ conference.

Register HERE

Speakers

Register HERE

Editor's note: Nicholas McGeehan is co-director of human rights research and advocacy group FairSquare, which works among other things on the nexus between sport and authoritarianism. He is a former senior researcher at Human Rights Watch and holds a PhD in international law from the European University Institute in Florence.

Boycotts, divestments and sanctions are each controversial and contentious in their own right, but when combined under the right conditions, they have explosive potential. BBC football presenter Gary Lineker found this out to his cost when he retweeted a call from Palestine’s BDS movement to suspend Israel from FIFA and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) until such time the Israeli state ends what they called “the crime of genocide it is perpetrating in Gaza” and its occupation of Palestinian territory. Lineker quickly deleted his retweet but not before the UK’s most popular right-wing tabloid newspaper, The Daily Mail, spotted it and renewed their fulminating campaign against Lineker’s support for political causes that run contrary to the Mail’s editorial positions. The Daily Mail does not oppose sporting boycotts, in fact judging from an article by its football columnist, Martin Samuel, it was an ardent supporter of Russia’s ejection from European football in the aftermath of its invasion of Ukraine. “Why should Russian football get to be part of the continent in which it has murdered innocents?,” asked Samuel and in that regard he was not alone and was echoing views heard across the political divide in the west at the time.

The west continues to boycott Russia, its companies have divested from Russia, and its governments are sanctioning Russia. This includes in the sporting arena where nobody batted an eyelid when Russian football teams were excluded from FIFA and UEFA competition, and its athletes excluded from IOC competition. So it seems obvious that it is not so much BDS tactics that offend people in certain quarters, but rather their target. Russia can be BDS’d until the cows come home, but BDS’ing Israel is beyond the pale. You can see how it might be hard to explain to a child.

Through an examination of the widely divergent responses to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Israel’s actions in Gaza, this piece argues that FIFA and the IOC have aligned themselves with the political positions of the countries of the global north. With reference to previous sporting boycotts, it demonstrates how an absence of rules has left FIFA and the IOC sailing rudderless into stormy geopolitical waters and argues that they need to institute rules to guide their responses to events of this gravity and magnitude. Dispensing once and for all with the canard that sport and politics can be kept apart would enable sport’s governing bodies to appropriately leverage their political power and not merely act as puppets of the global north. More...

Editor's note:

Daniela is a researcher at the Asser Institute in the field of sport and human rights. She has a

background in public international law and human rights law and defended

her PhD project entitled “Blurred Lines of Responsibility and

Accountability – Human Rights Abuses at Mega-Sporting Events” in April

2021 at Tilburg University. She also works as independent consultant in the field of sport and human rights for the Centre for Sport and Human Rights, or the European Parliament among other clients from the sports ecosystem

As Head of Policy and Outreach, Guido is in charge of the Centre for Sport & Human Rights engagement with governments, international and intergovernmental organisations and sports organisations. He represents the Centre at conferences, events and bilateral dialogues to reach new audiences and partners and raise public awareness and understanding of the Centre’s work .

On February 24,

2022, the Russian military invaded Ukrainian territory. What followed was an

escalation of the war, day by day, causing thousands of victims and forcing

millions of people to flee. On March 2, the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly adopted a resolution deploring "in the strongest possible terms" Russia's

aggression against Ukraine by a vote of 141 to 5, with 35 abstentions. On March

29, Russian and Ukrainian representatives met in Istanbul for another round of

negotiations. No ceasefire has been agreed and hostilities continue.

Many states,

international organizations and corporations quickly took measures in response

to this invasion. Hundreds of companies decided to withdraw

from Russia. Some countries decided to strengthen economic

sanctions against Russia and Belarus and to provide military and economic help

to Ukraine. Many civil society actors mobilised to organize and provide humanitarian

support for Ukraine. Interestingly, international sports organisations like the

International Olympic Committee (IOC), the Fédération Internationale de Football

Association (FIFA), World Athletics and many other international federations, issued

statements condemning the invasion and imposed bans and sanctions on Russian

and Belarussian sports bodies and athletes.

This blog post provides

an overview of the measures adopted by a number of international sports

federations (IFs) that are part of the Olympic Movement since

the beginning of the war and analyses how they relate to the statements issued

by the IOC and other sanctions and measures taken by international sports organisations

in reaction to (geo)political tensions and conflict.

More...

On Wednesday 14 July 2021 from 16.00-17.30 CET, the Asser International Sports Law Centre, in collaboration with Dr Marjolaine Viret, is organizing a Zoom In webinar on Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter and the right to free speech of athletes.

As the Tokyo Olympics are drawing closer, the International Olympic Committee just released new Guidelines on the implementation of Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter.

The latter Rule provides that ‘no kind of demonstration or political,

religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues

or other areas’. The latest IOC Guidelines did open up some space for

athletes to express their political views, but at the same time continue

to ban any manifestation from the Olympic Village or the Podium. In

effect, Rule 50 imposes private restrictions on the freedom of

expression of athletes in the name of the political neutrality of

international sport. This limitation on the rights of athletes is far from uncontroversial

and raises intricate questions regarding its legitimacy,

proportionality and ultimately compatibility with human rights standards

(such as with Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights).

This webinar aims at critically engaging with Rule 50 and its

compatibility with the fundamental rights of athletes. We will discuss

the content of the latest IOC Guidelines regarding Rule 50, the

potential justifications for such a Rule, and the alternatives to its

restrictions. To do so, we will be joined by three speakers, Professor Mark James from Manchester Metropolitan University, who has widely published on the Olympic Games and transnational law; Chui Ling Goh, a Doctoral Researcher at Melbourne Law School, who has recently released an (open access) draft of an article on Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter; and David Grevemberg, Chief

Innovation and Partnerships Officer at the Centre for Sport and Human

Rights, and former Chief Executive of the Commonwealth Games Federation

(CGF).

Guest speakers:

- Prof. Mark James (Metropolitan Manchester University)

- Chui Ling Goh (PhD candidate, University of Melbourne)

- David Grevemberg (Centre for Sport and Human Rights)

Moderators:

Free Registration HERE

Editor's note: Rusa Agafonova is a PhD Candidate at the University of Zurich, Switzerland

The Olympic Games are the cornerstone event of the Olympic Movement as a

socio-cultural phenomenon as well as the engine of its economic model. Having worldwide

exposure,[1] the Olympic Games guarantee

the International Olympic Committee (IOC) exclusive nine-digit sponsorship

deals. The revenue generated by the Games is later redistributed by the IOC

down the sports pyramid to the International Federations (IFs), National

Olympic Committees (NOCs) and other participants of the Olympic Movement through

a so-called "solidarity mechanism". In other words, the Games

constitute a vital source of financing for the Olympic Movement.

Because of the money involved, the IOC is protective when it comes to

staging the Olympics. This is notably so with respect to ambush marketing which

can have detrimental economic impact for sports governing bodies (SGBs) running

mega-events. The IOC's definition of ambush marketing covers any intentional and

non-intentional use of intellectual property associated with the Olympic Games as

well as the misappropriation of images associated with them without authorisation

from the IOC and the organising committee.[2]

This definition is broad as are the IOC's anti-ambush rules.More...

Editor’s

note: Thomas Terraz is a L.LM. candidate in

the European Law programme at Utrecht University and a former intern of the Asser International Sports Law Centre

1. Sport Nationalism is Politics

Despite all efforts, the

Olympic Games has been and will be immersed in politics. Attempts to shield the

Games from social and political realities are almost sure to miss their mark

and potentially risk being disproportionate. Moreover, history has laid bare

the shortcomings of the attempts to create a sanitized and impenetrable bubble

around the Games. The first

blog of this series examined the idea of the Games as a sanitized space and

dived into the history of political neutrality within the Olympic Movement to

unravel the irony that while the IOC aims to keep the Olympic Games ‘clean’ of

any politics within its ‘sacred enclosure’, the IOC and the Games itself are largely

enveloped in politics. Politics seep into the cracks of this ‘sanitized’ space through:

(1) public protests (and their suppression by authoritarian regimes hosting the

Games), (2) athletes who use their public image to take a political stand, (3) the

IOC who takes decisions on recognizing national Olympic Committees (NOCs) and awarding

the Games to countries,[1]

and (4) states that use the Games for geo-political posturing.[2] With

this background in mind, the aim now is to illustrate the disparity between the

IOC’s stance on political neutrality when it concerns athlete protest versus

sport nationalism, which also is a form of politics.

As was mentioned in part

one of this series, the very first explicit mention of politics in the Olympic

Charter was in its 1946 version and aimed to combat ‘the nationalization of

sports for political aims’ by preventing ‘a national exultation of success

achieved rather than the realization of the common and harmonious objective

which is the essential Olympic law’ (emphasis added). This sentiment was

further echoed some years later by Avery Brundage (IOC President (1952-1972))

when he declared: ‘The Games are not, and must not become, a contest between

nations, which would be entirely contrary to the spirit of the Olympic Movement

and would surely lead to disaster’.[3] Regardless

of this vision to prevent sport nationalism engulfing the Games and its

codification in the Olympic Charter, the current reality paints quite a

different picture. One simply has to look at the mass obsession with medal

tables during the Olympic Games and its amplification not only by the media but

even by members of the Olympic Movement.[4]

This is further exacerbated when the achievements of athletes are used for domestic

political gain[5] or when they are used to

glorify a nation’s prowess on the global stage or to stir nationalism within a

populace[6]. Sport

nationalism is politics. Arguably, even the worship of national imagery during

the Games from the opening ceremony to the medal ceremonies cannot be

depoliticized.[7] In many ways, the IOC has turned

a blind eye to the politics rooted in these expressions of sport nationalism

and instead has focused its energy to sterilize its Olympic spaces and stifle political

expression from athletes. One of the ways the IOC has ignored sport nationalism

is through its tacit acceptance of medal tables although they are expressly

banned by the Olympic Charter.

At this point, the rules restricting

athletes’ political protest and those concerning sport nationalism,

particularly in terms of medal tables, will be scrutinized in order to highlight

the enforcement gap between the two. More...

Editor’s

note: Thomas Terraz is a fourth year LL.B.

candidate at the International and European Law programme at The Hague

University of Applied Sciences with a specialisation in European Law. Currently

he is pursuing an internship at the T.M.C. Asser Institute with a focus on

International and European Sports Law.

Since its inception, the Olympic Movement, and in particular the

IOC, has tirelessly endeavored to create a clean bubble around sport events, protecting

its hallowed grounds from any perceived impurities. Some of these perceived ‘contaminants’

have eventually been accepted as a necessary part of sport over time (e.g.

professionalism in sport),[1]

while others are still strictly shunned (e.g. political protest and

manifestations) and new ones have gained importance over the years (e.g.

protection of intellectual property rights). The IOC has adopted a variety of

legal mechanisms and measures to defend this sanitized space. For instance, the IOC has led massive efforts

to protect its and its partners’ intellectual property rights through campaigns

against ambush marketing (e.g. ‘clean venues’ and minimizing the athletes’

ability to represent their personal sponsors[2]). Nowadays,

the idea of the clean bubble is further reinforced through the colossal security

operations created to protect the Olympic sites.

Nevertheless, politics, and in particular political protest, has

long been regarded as one of the greatest threats to this sanitized space. More

recently, politics has resurfaced in the context of the IOC

Athletes’ Commission Rule 50 Guidelines. Although Rule 50 is nothing new, the

Guidelines stirred considerable criticism, to which Richard

Pound personally responded, arguing that Rule 50 is a rule encouraging ‘mutual

respect’ through ‘restraint’ with the aim of using sport ‘to bring people

together’.[3] In

this regard, the Olympic Charter aims to avoid ‘vengeance, especially misguided

vengeance’. These statements seem to endorse a view that one’s expression of

their political beliefs at the Games is something that will inherently divide people

and damage ‘mutual respect’. Thus, the question naturally arises: can the world

only get along if ‘politics, religion, race and sexual orientation are set

aside’?[4] Should

one’s politics, personal belief and identity be considered so unholy that they

must be left at the doorstep of the Games in the name of depoliticization and

of the protection of the Games’ sanitized bubble? Moreover, is it even possible

to separate politics and sport?

Even Richard Pound would likely agree that politics and sport are at

least to a certain degree bound to be intermingled.[5]

However, numerous commentators have gone further and expressed their skepticism

to the view that athletes should be limited in their freedom of expression

during the Games (see here,

here

and here).

Overall, the arguments made by these commentators have pointed out the hypocrisy

that while the Games are bathed in politics, athletes – though without their labor

there would be no Games – are severely restrained in expressing their own

political beliefs. Additionally, they often bring attention to how some of the

most iconic moments in the Games history are those where athletes took a stand

on a political issue, often stirring significant controversy at the time. Nevertheless,

what has not been fully explored is the relationship between the Olympic Games

and politics in terms of the divide between the ideals of international unity

enshrined in the Olympic Charter and on the other hand the de facto embrace of country

versus country competition in the Olympic Games. While the Olympic Charter

frames the Games as ‘competitions between athletes in individual or team events

and not between countries’, the reality is far from this ideal.[6] Sport

nationalism in this context can be considered as a form of politics because a

country’s opportunity to host and perform well at the Games is frequently used to

validate its global prowess and stature.

To explore this issue, this first blog will first take a historical

approach by investigating the origins of political neutrality in sport followed

by an examination of the clash between the ideal of political neutrality and

the reality that politics permeate many facets of the Olympic Games. It will be

argued that overall there has been a failure to separate politics and the Games

but that this failure was inevitable and should not be automatically viewed negatively.

The second blog will then dive into the Olympic Charter’s legal mechanisms that

attempt to enforce political neutrality and minimize sport nationalism, which

also is a form of politics. It will attempt to compare and contrast the IOC’s

approach to political expression when exercised by the athletes with its

treatment of widespread sport nationalism.More...

Editor's note: This report compiles the most relevant legal

news, events and materials on International and European Sports Law based on

the daily coverage provided on our twitter feed @Sportslaw_asser.

The Headlines

IOC Athlete Commission

releases its Rule 50 Guidelines for Tokyo 2020

The IOC Athlete Commission

presented its Rule 50 Guidelines for Tokyo 2020 at its annual joint meeting with the IOC Executive

Board. It comes as Thomas Bach had recently underlined the importance of political

neutrality for the IOC and the Olympic Games in his New Year’s message. Generally, rule 50 of

the Olympic Charter prohibits any political and religious expression by

athletes and their team during the Games, subject to certain exceptions. The

Guidelines clarify that this includes the ‘field of play’, anywhere inside the

Olympic Village, ‘during Olympic medal ceremonies’ and ‘during the Opening,

Closing and other official ceremonies’. On the other hand, athletes may express

their views ‘during press conferences and interview’, ‘at team meetings’ and

‘on digital or traditional media, or on other platforms. While rule 50 is

nothing new, the Guidelines have reignited a debate on whether it could be

considered as a justified restriction on one’s freedom of expression.

The IOC has made the case

that it is defending the neutrality of sport and that the Olympics is an

international forum that should help bring people together instead of focusing

on divisions. Specifically, Richard Pound has recently made the

argument that the Guidelines have been formulated by the athletes themselves and

are a justified restriction on free expression with its basis in ‘mutual

respect’. However, many commentators have expressed their skepticism to this

view (see here, here and here) citing that politics and

the Olympics are inherently mixed, that the IOC is heavily involved in politics,

and that the Olympics has often served as the grounds for some of history’s

most iconic political protests. All in all, the Guidelines have certainly been

a catalyst for a discussion on the extent to which the Olympics can be

considered neutral. It also further highlights a divide between athlete

committees from within the Olympic Movement structures and other independent

athlete representation groups (see Global Athlete and FIFPro’s statements on rule 50).

Doping and Corruption

Allegations in Weightlifting

The International

Weightlifting Federation (IWF) has found itself embroiled in a doping and

corruption scandal after an ARD documentary was aired early in

January which raised a wide array of allegations, including against the

President of the IWF, Tamás Aján. The documentary also included hidden camera interviews

from a Thai Olympic medalist who admits having taken anabolic steroids before

having won a bronze medal at the 2012 London Olympic Games and from a team

doctor from the Moldovan national team who describes paying for clean doping

tests. The IWF’s initial reaction to the documentary was

hostile, describing the allegations as ‘insinuations, unfounded accusations and

distorted information’ and ‘categorically denies the unsubstantiated’

accusations. It further claims that it has ‘immediately acted’ concerning the

situation with the Thai athletes, and WADA has stated that it will follow up

with the concerned actors. However, as the matter gained further attention in

the main stream media and faced increasing criticism, the IWF moved to try to ‘restore’ its reputation. In practice, this means

that Tamás Aján has ‘delegated a range of operation responsibilities’ to Ursual

Papandrea, IWF Vice President, while ‘independent experts’ will conduct a

review of the allegations made in the ARD documentary. Richard McLaren has been

announced to lead the investigation

and ‘is empowered to take whatever measures he sees fit to ensure each and

every allegation is fully investigated and reported’. The IWF has also stated

that it will open a whistleblower line to help aid the investigation.More...

Editor’s

note: Thomas Terraz is a fourth year LL.B.

candidate at the International and European Law programme at The Hague

University of Applied Sciences with a specialisation in European Law. Currently

he is pursuing an internship at the T.M.C. Asser Institute with a focus on

International and European Sports Law.

1

Introduction

The International Olympic Committee (IOC), after many years of ineffective

pushback (see here,

here

and here)

over bye law 3 of rule 40[1] of

the Olympic Charter (OC), which restricts the ability of athletes and their

entourage to advertise themselves during the ‘blackout’ period’[2]

(also known as the ‘frozen period’) of the Olympic Games, may have been gifted a

silver bullet to address a major criticism of its rules. This (potentially) magic

formula was handed down in a relatively recent

decision of the Bundeskartellamt, the German competition law authority,

which elucidated how restrictions to athletes’ advertisements during the frozen

period may be scrutinized under EU competition law. The following blog begins

by explaining the historical and economic context of rule 40 followed by the

facts that led to the decision of the Bundeskartellamt. With this background,

the decision of the Bundeskartellamt is analyzed to show to what extent it may serve

as a model for EU competition law authorities. More...

Editor's Note: Ryan Gauthier

is Assistant Professor at Thompson Rivers University in Canada. Ryan’s

research addresses the governance of sports organisations, with a

particular focus on international sports organisations. His PhD research

examined the accountability of the International Olympic Committee for

human rights violations caused by the organisation of the Olympic Games.

Big June 2019 for Olympic Hosting

On June 24, 2019, the International

Olympic Committee (IOC) selected Milano-Cortina to host the 2026 Winter Olympic

Games. Milano-Cortina’s victory came despite a declaration that the bid was “dead”

just months prior when the Italian government refused

to support the bid. Things looked even more dire for the Italians when 2006 Winter Games

host Turin balked at a three-city host proposal. But, when the bid was presented to

the members of the IOC Session, it was selected over Stockholm-Åre by 47 votes to 34.

Just two days later, the IOC killed

the host selection process as we know it. The IOC did this by amending two

sections of the Olympic Charter in two key ways. First, the IOC amended Rule 33.2, eliminating the

requirement that the Games be selected by an election seven years prior to the

Games. While an election by the IOC Session is still required, the

seven-years-out requirement is gone.

Second, the IOC amended Rule 32.2 to

allow for a broader scope of hosts to be selected for the Olympic Games. Prior

to the amendment, only cities could host the Games, with the odd event being

held in another location. Now, while cities are the hosts “in principle”, the

IOC had made it so: “where deemed appropriate, the IOC may elect several

cities, or other entities, such as regions, states or countries, as host of the

Olympic Games.”

The change to rule 33.2 risks

undoing the public host selection process. The prior process included bids

(generally publicly available), evaluation committee reports, and other

mechanisms to make the bidding process transparent. Now, it is entirely

possible that the IOC may pre-select a host, and present just that host to the

IOC for an up-or-down vote. This vote may be seven years out from the Games,

ten years out, or two years out. More...