This year’s FIFA congress in Sao Paulo should not be

remembered only for the controversy surrounding the bid for the World Cup 2022

in Qatar. The controversy was surely at the centre of the media coverage, but

in its shadow more long-lasting decisions were taken. For example, the new Regulations on

Working with Intermediaries was approved, which is probably the most

important recent change to FIFA regulations. These new Regulations will

supersede the Regulations on Players’

Agents

when they come into force on 1 April 2015. In this blog post we compare the old and

the new Regulations followed by a short analysis and prospective view on the

effects this change could have.

The Road to the

New Regulations

Players’ agents, or “intermediaries” should we use

FIFA’s new terminology, provide their services to football players and clubs to

conclude employment contracts and transfer agreements. FIFA has been regulating

this activity since it introduced the first Regulations on players’ agents on 1

January 1996. Even though the Regulations were amended several times since then,

it is only during the last five years that a permanent consultation process was

put in place. According to a FIFA

press release, the consultation process involved member associations,

confederations, clubs, FIFPro and professional football leagues. Surprisingly

however, the press release does not mention whether agent stakeholders, such as

Pro Agent were also consulted. The

ultimate objective of these consultations was to propose a new system that is

more transparent and simpler in its implementation and administration.[1] At

the beginning of 2013, a Sub-Committee for Club Football was set up to deal

exclusively with the issue of reforming the Players’ Agents Regulations. Later

on that year the Committee presented a draft for the FIFA Congress 2013 based on the following three

findings:

The current licensing system should be abandoned

A set of minimum standards and requirements must be established in FIFA’s future

regulatory framework

A registration for intermediaries must be set up [2]

The draft Regulations were finally approved by the

FIFA Executive Committee on 21 March 2014 and by the FIFA Congress on 11 June

2014. Furthermore, the three objectives outlined are supposedly reflected in

the new Regulations.

A Rough

Comparison of the Old and New Agents/Intermediaries Regulations

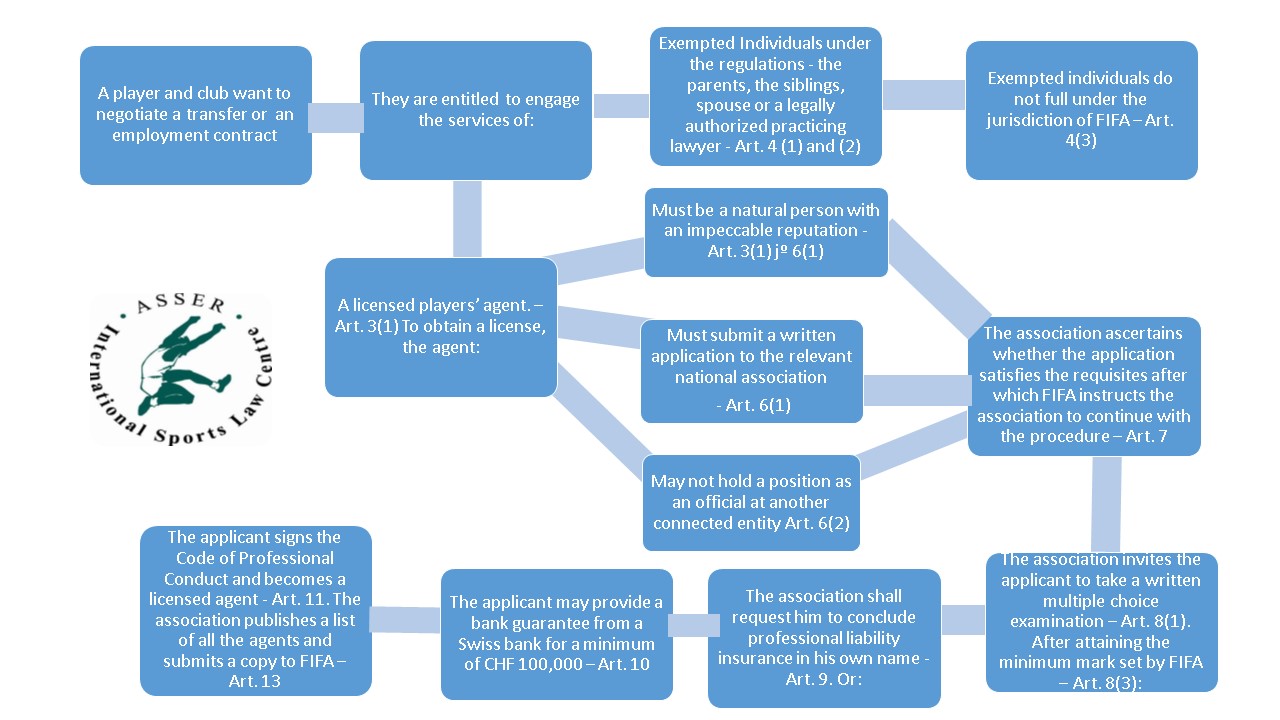

In the following flowcharts we have summarized the key

requirements enshrined in both the old and the new agents/intermediaries FIFA

regulations. This provides a clear comparison of the differences and

similarities existing between the two regulatory frameworks.

Flowchart: Becoming an Agent under the Old FIFA

Regulations

FlowchartRegulationsPlayers'Agents.jpg (179.7KB)

Flowchart: Becoming

an Intermediary under the New FIFA Regulations

FlowchartRegulationsonWorkingwithIntermediaries.jpg (146.5KB)

By abandoning the old licensing system, the procedure

to become an intermediary becomes much simpler than before. The applicant does

not have to undergo an examination by FIFA anymore, nor does he need to

conclude a professional liability insurance in his own name or provide a bank

guarantee from a Swiss bank for a minimum amount of CHF 100,000. Furthermore,

in contrast to the old Regulations, legal persons can now also act as

intermediaries. Thus, in the near future we can expect players such as

Cristiano Ronaldo, Radamel Falcao and coach Jose Mourinho to be represented by

the agents’ company GestiFute rather than simply the agent Jorge Mendes.

However, it should be noted that FIFA’s new

Regulations on Working with Intermediaries are to be considered as minimum

standards or requirements. In accordance with Art. 1(3), the right of

associations to go beyond these minimum standards/requirements is preserved. In

other words, national associations can set higher thresholds for becoming an

intermediary should they wish for. In order to better understand the practical

reality of the regulation of agents it is therefore necessary to analyse to

what extent different associations set different standards and requirements.

Registration

Under the new Regulations, the national associations will

still be responsible for adopting a registration system regarding the

intermediaries. However, several important changes between the old and the new

Regulations can be deciphered, including the contractual terms between the

intermediary and the player/club and the remuneration terms.

Contractual

terms

Under the old Regulations, the representation contract

between the agent and the player and/or club would only be valid for a maximum

period of two years. Moreover, the contract could be extended for another

period of maximum two years (Art. 19(3) of the old Regulations). According to

Art. 3 of the new Regulations, "intermediaries must be registered in the

relevant registration system every time they are individually involved in a

specific transaction". Players and clubs disclose all the details to the association

when called upon. Thus, by allowing players not to be contractually bound to a

specific intermediary for a specific period of time, the bargaining position of

the player when engaging the services of an intermediary is likely to increase.

Remuneration

terms

In both the old as well as in the new Regulations the

amount of remuneration shall be calculated on the basis of the player’s basic

gross income. [3] Nonetheless,

where under the old Regulations the remuneration is calculated on the basis of

the player’s annual income, under the

new Regulations the remunerations is calculated on the basis of the player’s

income for the entire duration of the

contract. Moreover, as stipulated in Art. 7(3)a) of the new Regulations,

the “total amount of remuneration per transaction due to intermediaries (…)

should not exceed 3% of the player’s basic gross income for the entire duration

of the contract”. Secondly, the new Regulations prohibit any payment to

intermediaries when the player is a minor.[4] With

the new provisions on remuneration FIFA hopes to avoid that intermediaries

exploit players. Indeed, in many countries it is still common practice for players

to (unknowingly) sign contracts with their agents forcing them to pay a much

higher share of their income. This was perfectly possible under the old

Regulations since it did not provide a remuneration limit due to the players’

agents and there was no prohibition regarding remuneration to the agent when

the player is a minor and should be way more difficult under the new

Regulations.

Conclusion

With the new

Regulations FIFA attempts not to regulate access to the activity anymore, but

instead to shape the practice itself: players and clubs are authorised to

choose any parties as intermediaries and can change intermediary at any moment

since they are not bound by a contract with the intermediary. Furthermore, with

the remuneration limit of 3% of the player’s income FIFA aims to limit the risk

of players being exploited by their intermediaries.

Even though FIFA has explicitly stated the new

Regulations will not deregulate the profession, it seems that it is placing the

main responsibility to regulate onto the national associations. Not only will

all the national associations be required to introduce a registration system,

but they are also responsible for enforcing the rules and for imposing sanctions

in case the new Regulations are breached. As we have seen, when selecting an

intermediary, players and clubs shall act with due diligence. However, the

definition of the interpretation of the notion of due diligence is left open and

could differ from country to country.

With the game of football becoming ever more

globalised and with an ever increasing amount of international transfers of

players, regulating the profession of agent/intermediary at the national level is

becoming increasingly difficult. In this context, FIFA has adopted a surprising

orientation by delegating the responsibility to regulate the profession to the

national associations.

[1] http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/organisation/administration/news/newsid=2301236/

[2] http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/organisation/bodies/congress/news/newsid=2088917/

[3] The Regulations on Players’ Agents, Art. 20(1)

and the Regulations on Players’ Agents, Art. 7(1)

[4] The Regulations on Players’ Agents, Art. 7(8)