Editor's note: Branislav

Hock (@bran_hock) is PhD Researcher at the Tilburg Law and Economics Center at Tilburg

University. His areas of interests are transnational regulation of corruption, public

procurement, extraterritoriality, compliance, law and economics, and private

ordering. Author can be contacted via email: b.hock@uvt.nl.

This blog post is based on a paper

co-authored with Suren Gomtsian, Annemarie Balvert, and Oguz Kirman.

Game-changers that lead to financial

success, political revolutions, or innovation, do not come “out of the blue”;

they come from a logical sequence of events supported by well-functioning

institutions. Many of these game changers originate from transnational private

actors—such as business and sport associations—that produce positive spillover

effects on the economy. In a recent paper forthcoming

in the Yale Journal of International Law, using the example of FIFA, football’s

world-governing body, with co-authors Suren Gomtsian, Annemarie Balvert, and

Oguz Kirman, we show that the success of private associations in creating and

maintaining private legal order depends on the ability to offer better

institutions than their public alternatives do. While financial scandals and

other global problems that relate to the functioning of these private member

associations may call for public interventions, such interventions, in most

cases, should aim to improve private orders rather than replace them.

FIFA example – from gentlemen’s agreements to a rich global

regulator

FIFA is the

governing body for football (or soccer, as it is known in some countries). Founded

in 1904 under Swiss law by seven football associations, just 40 years ago, FIFA

was a small gentlemen's club with a staff of 11, far from politics, which

produced little cash. Since then, it has evolved into a powerful organization

generating billions of dollars in annual revenues through sales of media and

marketing rights; now it employs hundreds. The rise of FIFA has been a

continuous process that was made possible by the reluctance of states and

supra-national organizations such as the European Union (EU) to intervene in

the governance of sport, particularly football. Hence, supported by and

benefitting from the special treatment of sports, FIFA filled the regulatory

gap and strengthened its status as a private regulator.

Besides the rules of the game, FIFA’s

legal order includes privately-designed rules of cooperation and a complex

organizational structure that spans every involved party including players,

clubs, coaches, managers, club investors, officials, sponsors, and spectators. The

centerpiece of the relations regulated by the rules of FIFA are

employment-related questions. Most

importantly, FIFA’s Transfer Regulations create strong tensions between FIFA’s regulatory autonomy

and public orders such as the sovereign jurisdictions of FIFA’s member

associations and supra-national organizations. Tensions between

different levels of employment rules are especially visible in matters related

to equality and/or non-discrimination of workers, the treatment and

qualification of minors, the freedom to choose employment, and the freedom of

movement. For example, the inability of players to terminate their contracts

without cause, before expiry and without paying compensation, is in stark

contrast with traditional employment laws, according to which employees are

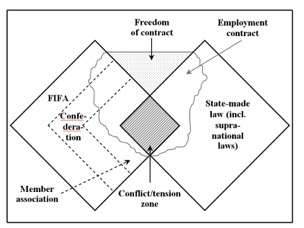

free to end employment without cause by prior notice. Figure below illustrates

the relationships between the different levels of “football ordering” and

public ordering when it comes to labor rules.

The Relationship of

Labor Rules in Football

Furthermore, FIFA has also private dispute

resolution venues and sophisticated system of sanctions and incentives

promoting compliance with the decisions of the private order’s dispute resolution

bodies. Possible sanctions vary but they are leveraged by the

monopoly power of FIFA. Consider the right of FIFA to suspend a member

association for a specific period or expel it fully from FIFA for failure to

comply with its obligations, including an obligation to comply with FIFA or CAS

decisions. Given FIFA's monopoly, this, in fact, means that national teams and

licensed clubs from the suspended or expelled country cannot participate in any

organized game. As a consequence,

FIFA has been able to maintain cooperation among all involved actors, yet,

along with the increasing commercial dimension, the incentives of states and

other public orders, particularly the EU, to intervene have grown.

Integrity vs. legal order

The fact that FIFA is undermined by

corruption is nothing surprising. Prof. Alina Mungiu-Pippidi shows that

the average public integrity in more than 200 countries whose soccer

associations are the FIFA constituents “is just 5, on a scale where New Zealand

has ten and Somalia 1” […] “Were FIFA a country, it would clearly not be in the

upper half, but somewhere near Brazil, whose officials seem to have been waist

deep in its corruption, and which ranks around 121, with a 4.2”. FIFA’s administrative structure, certainly,

needs reforms that will improve its financial stability and decrease corruption

risks within the organization. These reforms, indeed, may require “public

nudge” by the enforcement of extraterritorial “anti-mafia” statutes such as the

US Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO)

that played the central role in the so-called FIFAGate.

Moreover, in the light of “the second FIFAGate”—six months after the original scandal, a number of FIFA

officials that replaced the old leadership were charged with a 92-count

indictment—and after the recent neutralization of its internal corruption

investigations (see here),

more radical “public nudge” may be desirable. Indeed, these developments, as

was discussed in this blog

some time ago, may call for a more powerful intervention by, for example, the

EU, to impose ‘certain basic “constitutional” requirements’ to FIFA.

Nevertheless, while FIFA may need

“public help” to clean its house and improve some areas of its legal order, no

public order is a better alternative. Common rules spanning across borders,

predictable contractual relations, and incentives to invest in training young

players are only some advantages made possible by FIFA’s tailored rules of

behavior. These advantages would be lost if public interventions would crash

the FIFA order and replace it by a patchwork of national laws, unstable

contractual relations, more costly dispute resolution and enforcement

mechanisms, and limited ability to encourage talent development. Therefore,

while FIFA as an administrative organization may generally be considered as more

corrupt than an average government, it has been able to offer harmonized

institutions that in many cases are better accustomed to the needs

of the involved parties than their state-made alternatives, which often are

based on one-size-fits-all approach and lack certainty of application.

Public orders as the reversed civil

society

It does not mean that public orders

such as the EU and nation states should do nothing. Private entities often need

a “public nudge” not only to prevent excesses, but also to maintain incentives

to produce rules that reflect new economic and social developments. In numerous

writings (for an overview see Katz),

law-and economics scholars indicate that while in principle private orders

should be best left alone, states should limit the potential of powerful

interest groups to undermine the roots of private orders such as FIFA. Who, how,

and when should determine the benchmark of what is excessive is difficult, and law-and

economics has declined to offer a general theory of the role of public orders

in nudging private orders to limit interest groups’ power. Nevertheless, determining

the role of public orders is no more difficult than the question what civil

society should do when it comes to the performance of nation states.

In the context of nation states, the

key role in limiting the power of elites belongs to the civil society. In case

of monopolistic orders such as FIFA’s, however, there is often no direct

representation of various actors inside such orders. Shouldn’t, then, states and

the EU assume the role of a reversed civil society when interacting with large

and successful private orders? In practice, particularly the EU is more and

more involved in an informal co-determination of football-related regulation

(for similar argument see here).

For example, the recent social dialogue in European football, brokered

by the EU Commission, is an example how public orders can fulfill their role as

reversed civil society. The EU Commission, instead of intervening directly and

regulating sports, encouraged, and should do so much more, various stakeholder

groups, such as the European Club Association and FIFPro, to engage in a

dialogue with the purpose of improving the practices of player protection

(however, it is true that the EU Commission had a way deeper impact through EU

competition law, see Duval).

For the private order itself participation in this dialogue and active

encouragement of the enforcement of its results is the best way to guarantee its

role as a supplier of rules (see generally Colucci &

Geeraert). In contrary, refusal to accommodate certain mechanisms,

and mainly these that effectively limit FIFA’s executives’ power (e.g. Ethics

Committee), may lead to a forceful, but legitimate, public intervention with

possibly tragic consequences for the world of football.

Conclusion: Taking over fallen

FIFA

What is so fascinating about FIFA is that it

exemplifies how a very small number of enthusiastic people could set a

mechanism that is ultimately able to create institutions that aim to regulate

behavior of involved actors globally as well as to keep them away from regular

courts. FIFA is an example of an order that has created huge economic and

social value by being able to overcome many hurdles that prevented countless

other member associations from creating their own orders (think of lawyers or

investment bankers, for example). The fact that such order locks-in all

involved football actors, despite some, such as small teams, benefiting

significantly less by their participation than others, suggests that there is a

value, despite FIFA’s monopoly power, that alternatives cannot offer. Some of them, such as

increased certainty, are in the interests of all involved actors, whereas

others, such as commitment to enforce contractual practices or training

compensation awards, are more preferred by sophisticated actors (i.e. clubs and

prominent footballers) and small clubs, respectively. This, though not allowing

to state plainly that the private order is maximizing the welfare of all

involved actors, also does not justify arguments for abandoning the current

system in favor of state laws. In contrary, failure to accommodate mechanisms

that limit the power of inside interest groups might undermine the order by

giving incentives to interest groups to advocate public orders’ involvement,

thereby putting an end to the monopoly of FIFA’s order, and possibly its destruction.