2015 was a good year for

international sports law. It started early in January with the Pechstein

ruling, THE

defining sports law case of the year (and probably in years to come) and ended

in an apotheosis with the decisions rendered by the FIFA Ethics

Committee against Blatter and Platini. This blog will walk you through the

important sports law developments of the year and make sure that you did not

miss any.

The Court of

Arbitration for Sport challenged by German Courts

The more discrete SV Wilhelmshaven ruling came

first. It was not even decided in 2015, as the ruling was handed out on 30

December 2014. Yet, unless you are a sports law freak, you will not have taken

notice of this case before 2015 (and our blog). It is not as well known as the Pechstein ruling, but it is challenging

the whole private enforcement system put in place by FIFA (and similar systems

existing in other SGBs). Indeed, the ruling foresees that before enforcing a

sanction rendered by FIFA, the national (or in that case regional) federation

must verify that the award underlying the sanction is compatible with EU law.

The decision has been appealed to the Bundesgerichtshof (BGH) and a final

ruling is expected in 2016.

Later on, in January, the

Oberlandesgericht München dropped its legal bomb in the Pechstein case. The court refused to recognize the CAS award

sanctioning Claudia Pechstein with a doping ban, as it was deemed contrary to

German antitrust rules. The reasoning used in the ruling was indirectly

challenging the independence of the CAS and, if confirmed by the BGH, will trigger

a necessary reform of the functioning and institutional structure

of the CAS. Paradoxically, this is a giant step forward for international

sports law and the CAS. The court acknowledges the need for CAS arbitration in

global sport. However, justice must be delivered in a fair fashion and the

legitimacy of the CAS (which relies on its independence from the Sports

Governing Bodies) must be ensured (see our long article on the case here).

We will see how the BGH will deal

with these cases in 2016. In any event, they constitute an important warning

shot for the CAS. In short, the CAS needs to take EU law and itself seriously.

If it truly addresses these challenges, it will come out way stronger.

The new World

Anti-Doping Code and the Russian Doping Scandal

On the doping front, 2015 is the

year in which the new World Anti-Doping Code (WADC) came into force (see our Blog Symposium). The Code introduces substantial

changes in the way the anti-doping fight is led and modifies the sanction regime applicable in case of an adverse

analytical finding. It is too early to predict with certainty its effects on

doping prevalence in international sports. For international sports lawyers,

however, it is in any event a fundamental change to the rules applicable to anti-doping

disputes, which they need to get closely acquainted with.

The new World Anti-Doping Code was

largely overshadowed by the massive doping scandal involving Russian sports,

which was unleashed by an ARD documentary (first released in 2014) and revived

by the crushing report of the Independent Commission

mandated by the World Anti-Doping Agency to investigate the matter. This

scandal has shaken the legitimacy of both the anti-doping system and the International Association of Athletics

Federations (IAAF). It has highlighted the systematic shortcomings of

the anti-doping institutions in Russia, and, the weakness of the control

exercised on these institutions at a transnational level, be it by IAAF or

WADA.

In 2015 again, doping proved to be a

scourge intimately linked with international sports. The confidence and the

trust of the public, and of clean athletes, in fair sports competitions is anew

put to the test. WADA, which was created in the wake of another massive doping

scandal in the nineties, has shown its limits. In practice, the

decentralization of the enforcement of the WADC empowers local actors, who are

very difficult to control for WADA. Some decide to crackdown on Doping with

criminal sanctions (see the new German law adopted in December 2015), others

prefer to collaborate with their national athletes to improve their

performances. The recent proposals at the IOC level aiming at shifting

the testing to WADA can be perceived as a preliminary response to this problem.

Yet, doing so would entail huge practical difficulties and financial costs.

EU law and sport: 20

years of Bosman and beyond

2015 was also the year in which the

twentieth anniversary of Bosman was

commemorated through multiple conferences and other sports law events. The

ASSER International Sports Law Centre edited a special edition of the Maastricht Journal of European

and Comparative Law and a book celebrating the legacy of the ruling is

forthcoming with the publisher Springer. The ruling did not have the dramatic

effects predicted at the time of the decision, since football is still alive

and kicking. Surely, it has given way to new challenges and sharply accelerated

the transnationalization of football (and sport in general). A key legacy of Bosman is that this

transnationalization, which goes hand in hand with the commercialization of

sport, cannot side-line an essential category of stakeholders: the athletes.

It is with this spirit in mind, and

a little push of the ASSER International Sports Law Centre, that the European Commission

decided to open an investigation into the rules of the International

Skating Union (ISU) barring, under the threat of a life ban, speed skaters (and

any other affiliate) from joining speed skating competitions which are not

condoned by the ISU. Though the case is rather low profile outside of the

Netherlands, this is an important step forward for the EU Commission, as it had

not opened an EU competition law investigation in sporting matters in almost 15

years. Many other competition law complaints (e.g. TPO or Formula 1) involving sport are currently pending in

front of the EU Commission, but it is still to decide whether it will open a

formal investigation. 2015 is also the year in which we have desperately expected the release of the EU State aid

decisions regarding football clubs, and amongst them Real Madrid, but in the

end this will be a matter for 2016.

FIFA and the chaotic

end of the Blatter reign

FIFA is not the only SGB to have put

an abrupt end to the (very) long reign of its great leader (think of the messy

downfall of Diack at the IAAF). Yet, when talking about FIFA and

football, the resonance of a governance crisis goes well beyond any other. It

is truly a global problem, discussed in nearly all news outlets. This

illustrates very much how a Swiss association became a global public good, for

which an Indian, Brazilian, American or European cares as much as a Swiss, who

is in traditional legal terms the only one able to influence FIFA’s structure

through legislation. The global outrage triggered by the progressive release by

the US authorities of information documenting the corrupt behaviour of FIFA

executives has led to two immediate consequences: a change of the guard and a

first reform of the institution.

There are now very few FIFA Executive Committee members left who were

present in 2010 for the election of Qatar as host city for the 2022 World Cup.

The long-time key figures of FIFA, Blatter, Platini and Valcke, are unlikely to

make a comeback any time soon. And, the upcoming February election of the new

FIFA president is more uncertain than ever with five candidates remaining. Simultaneously, FIFA has announced some governance reforms, which aim

at enhancing the transparency of its operation and the legitimacy of its

decision-making. We are living through a marvellous time of glasnost and

perestroika at FIFA. The final destination of this transformative process remains

unknown. There are still some major hurdles to overcome (starting with the one

association/one vote system at the FIFA congress) before FIFA is truly able to

fulfil its mission in a transparent, accountable and legitimate manner. We hope

it will be for 2016!

The ASSER

International Sports Law Blog in 2015

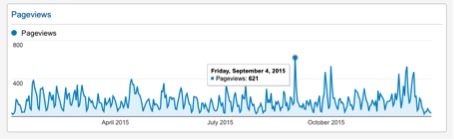

Finally, a few words on our blog in

2015. In one year we have published 60 posts, our most-read-blog concerned the Pechstein ruling that was read 3054 times.

Our peak day was reached on 4

September with 621 page views (thanks to a great post on the Essendon

case by @jrvkfootball).

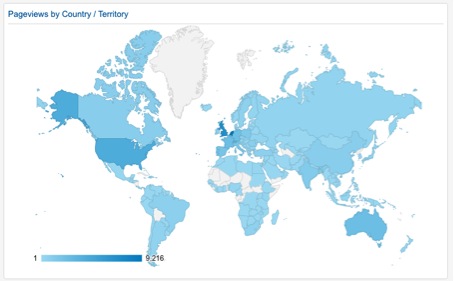

Our readers are based all around the

world, but the majority is based in the EU and the US.

We hope to

be able to keep you interested and busy in 2016 and we wish you a great year!

The ASSER

International Sports Law Blog Team