'Can't fight corruption with con tricks

They use the law to commit crime

And I dread, dread to think what the future

will bring

When we're living in gangster time'

The Specials - Gangsters

The pressing need for change

The

Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) of the Council of Europe (CoE), which is composed

of 318 MPs chosen from the national parliaments of the 47 CoE member states,

unanimously adopted a report entitled ‘the reform of

football’

on January 27, 2015. A draft resolution on the report will be debated during the

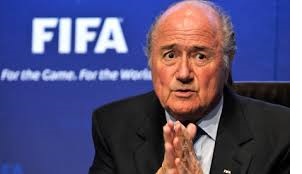

PACE April 2015 session and, interestingly, (only?) FIFA’s president Sepp

Blatter has been sent an invitation.

The PACE report

highlights the pressing need of reforming the governance

of football by FIFA and UEFA respectively. Accordingly, the report contains

some interesting recommendations to improve FIFA’s (e.g., Qatargate[1]) and

UEFA’s governance (e.g., gender representation). Unfortunately, it remains unclear

how the report’s recommendations will actually be implemented and enforced.

The report is a

welcomed secondary effect of the recent Qatargate directly involving former

FIFA officials such as Jack Warner, Chuck Blazer, and Mohamed Bin Hammam[2] and

highlighting the dramatic failures of FIFA’s governance in putting its house in

order. Thus, it is undeniably time to correct the governance of football by FIFA

and its confederate member UEFA – nolens

volens. The real question is how to do it.

Photograph:

Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images Photograph:

Octav Ganea/AP

The main recommendations of the report

In order to successfully

investigate and disciplinary sanction violations made by its members, the

report calls on FIFA and UEFA to revamp their institutions. Issues like

corruption, nepotism, cronyism, conflict of interests can only be solved if:

- The rules and decisions are clear, transparent and accountable (i.e. sanctioned) at a central level (Congress)

The flow of money is clear, transparent and accountable (i.e. sanctioned) at a central level (Congress)

Those who are in charge could be held accountable in a judicial or democratic, transparent and clear way before Congress

- The duration of the terms of office should be limited at all levels (President, Congress, Committees)

The rules and decisions made by independent FIFA/UEFA officials should be made ‘for the good of the game’ and not for personal gains

Possible conflicts of interests should be prevented

Gender equality with regard to democratic representation (Congress, Committees).

The report’s lack of clarity on the role of

Switzerland

In order to

implement the report’s recommendations, it is necessary to fully appreciate the

essential role Switzerland could play because, inter alia, FIFA and UEFA are

both associations under Swiss law.

While taking into account the upcoming implementation of Lex FIFA i.e. the

criminalisation of corruption in sport in Switzerland, one needs also to

analyse the potential role of Swiss private law to ensure a comprehensive implementation

of the report’s recommendations on reforming the governance of football by FIFA

and UEFA.

Good governance, corporate governance or association

governance?

‘Good

governance’ should be distinguished from ‘corporate governance’. The main and

essential difference between the two is that the former concerns the protection

of the public interest and the latter the protection of the corporation

concerned. Accordingly, the set of duties, responsibilities and competences of,

e.g., public law authorities are different from those who serve in a commercial

enterprise. Considering the public and private law context and the different

demands with regard to using the available instruments thereof, it is important

to discern the differences between good governance and corporate governance.[3]

According to

the European Commission ‘[c]orporate governance defines relationships between a

company’s management, its board … and its … stakeholders[4].

It determines the way companies are managed and controlled’[5] by

those stakeholders for the former’s and

the latter’s interest.

In principle,

corporate governance is mainly the (social) responsibility of the respective

corporation[6]

whereby those stakeholders play a crucial role to ensure that certain standards[7]

such as transparency and accountability – with regard to, e.g., FIFA’s and

UEFA’s economic and rule-making activities – would be respected in accordance

with mandatory rules of national and EU law[8].

All international sports governing bodies located in Switzerland such as

FIFA and UEFA have been

recognized as private law associations under Article 60 et seq. of the Swiss Civil Code (CC). Since

1981, Switzerland has also recognized the public law status of the

International Olympic Committee (IOC).[9]

Under Swiss

law, an association could be a profit-organization that may make turnovers or

profits comparable to commercial enterprises.[10] Essentially,

however, a corporation differs from an association, namely the former has to be

financially accountable to its shareholders whereas the latter is required to be

democratically and financially accountable to its members.[11]

In order to ensure that those members make use of their membership rights, it

is fundamental that the decision-making process with regard to anti-corruption

compliance structures and democratic structures are strictly adhered in

accordance with mandatory rules of law. Accordingly, it may also be a starting

point for associations to act in accordance with the principles of ‘association

governance’ if they were – indeed – implemented in mandatory law and applied

correctly.[12]

Constraints to association governance

As one of the state parties to the European Convention on

Human Rights (ECHR), Switzerland is inter alia bound by Article 11 of the

ECHR i.e. the fundamental right to freedom of (assembly and) association, which

is subject to restrictions that are in accordance with the law and necessary in

a democratic society. Accordingly, those associations have a restricted competence[13]

to set the rules, to apply and to enforce them uniformly to their members.[14]

According to

Article 23 Federal Constitution (FC), a private law association with a non-economic

objective (i.e. political, religious, scientific, cultural, social or

non-profit) has the right of freedom of association i.e. the right to establish

or dissolve, to voluntarily be (come) a member or to leave and to participate

in the association’s activities, which is not subject to state approval or

state supervision. [15]

As profit associations are only protected by the right of economic freedom

pursuant to Article 27 FC, it is of vital importance for non-profit associations

not to aim for monetary or financial benefits for its members.[16]

FIFA’s intent

to exist as a non-profit organization is apparent from their articles of

association.[17]

According to Article 2(a) FIFA statutes, its main objective is: ‘[…] to improve

the game of football constantly and promote it globally in the light of its

unifying, educational, cultural and humanitarian values, particularly through

youth and development programmes’. UEFA has a corresponding objective pursuant

to Article 2 UEFA statutes. As long as the surplus of revenues will be spent on

its non-commercial objectives under those articles of association, the

non-profit status of FIFA – and, mutatis

mutandis, UEFA – would not be challenged by Switzerland[18]. However,

as a legislator, a judicator and as a state party to the CoE, Switzerland should

critically assess those associations’ non-profit objectives and the significant

surplus from their economic activities plus the distributions thereof in view

of the report’s recommendations on financial

transparency and accountability in order to respect the – underlying – association

governance principles.[19]

FIFA and UEFA[20]

are both established and registered[21]

as private law associations under Article 60 et seq. CC[22] and,

moreover, bound to respect the Swiss mandatory rules of law under Article 63(2)

CC. Thus, mandatory rules cannot be disregarded by the articles of association

i.e the self-regulatory framework of FIFA and UEFA. If an association’s

resolution were to breach mandatory rules, it would be either voidable (i.e. to

be challenged within a month of the notification) or null and void (i.e. to be raised

at any time) under Article 75 CC.[23]

In case the

articles of association do not address a particular issue, the non-mandatory

rules of law would apply.[24]

In particular, it should be noted that Articles 64-69b CC mostly[25] refer

to mandatory procedural rules with regard to the articles of association. For

instance, an association is required to have two organs, namely the general

meeting of members that has supremacy over all other organs (Article 64(1) CC)

and a committee consisting of members – and non-members if not explicitly

forbidden by the articles of association[26] –

that are elected by the supreme governing body (Article 69 CC). Other organs

may be established pursuant to the articles of association.[27]

In other words,

it is up to the, e.g., FIFA articles of association to self-regulate the

composition, the independence of the Ethics Committee’s members and the

transparency of its work. It is therefore not clear how this particular recommendation

(please consider p. 8 of the report) can actually be implemented and enforced

by the Swiss authorities. A similar assessment could be made, mutatis mutandis, with regard to all the

other recommendations of the report.

Civil liability

Apart from the

aforesaid memberships’ rights deriving from the decision-making process with

regard to anti-corruption compliance structures and democratic structures,

associations could also be held liable by their members because a membership is

a contractual agreement between two private parties. In other words, the extra-legal

part of association governance may be corrected by the rules of civil liability

(including tort).

In accordance

with Article 1 in conjunction with Article 155(f) of the Private International

Law Act (PILA), Articles 52-59 (‘legal entities’) and Articles 60-79

(‘associations’) CC are applicable to all

members of both associations.[28] If

a private person or legal entity decides to be(come) a member of a private law

association, the respective articles of association, regulations or decisions

are contractually binding. Apart from membership contracts, there are – of

course – other forms of private law’ relationships available whereby one may contractually

be bound (in[29])directly

to the FIFA or UEFA rules or decisions like, e.g., labour contracts, commercial

contracts, player’ licences or host city agreements (e.g., Qatargate).

In this regard,

the mandatory rules of civil law include, in particular public policy, bona mores and the protection of

personality rights.[30]

Given that the public policy restrictions have already

been assessed in an earlier blog post[31],

this blog will specifically focus on bona

mores and the protection of personality rights.

As regards to bona

mores, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court ruled that in case an article of

association contains a third party’s veto right regarding all decisions of the

association’s general assembly, it would be null and void for violating bona mores and the right of autonomy of

associations.[32]

In reference to

the Swiss notion of personality rights

(e.g., the right to professional fulfilment through sporting activities, or the

right to economic freedom[33])[34],

which must be regarded as the equivalent of human rights horizontally applied

to private law’ relationships, Article 27 CC stipulates that ‘[n]o person can

wholly or partially renounce its capacity to have rights and to effect legal

transactions’.[35]

Accordingly, if it cannot be established that the law, the athlete’s consent or

the existence of an overriding public/private interest may justify an

infringement to, e.g., an athlete’s right to economic freedom (i.e. restraint

of trade), it must be regarded as null and void under Article 28 CC.[36]

Hence, as legislator and as State party to the CoE, Switzerland should have the

duty to critically assess whether FIFA or UEFA may infringe their members’ contractual

rights as protected by mandatory rules of law, in particular public policy and the

protection of personality rights (i.e. contractual freedoms) in the light of the

report’s recommendations on financial and

on democratic transparency in order to respect the – underlying – association

governance principles.

Criminal liability

As regards the impact

of mandatory rules of criminal law on international sports

federations based in Switzerland, the first package

of Lex FIFA - that will enter into force in the first half of 2015 if

uncontested (i.e. a referendum[37])

- defines their respective ‘presidents’ as ‘politically-exposed persons’

(PEPs) i.e. persons with a prominent public function[38].

As PEPs are in a position to potentially commit financial offences (money

laundering or corruption), banks are required to closely monitor those accounts

(and of their families!) for any suspicious financial transaction. If PEPs and/or

their families were to receive cash payments greater than CHF100,000, the

respective bank would be obliged to identify them, to keep a record of the

transactions and to clarify the background thereof. In case there is any

evidence of criminal activities, the bank must report the unusual transactions

to the Swiss authorities.[39]

However, and surprisingly, the first package of Lex FIFA does not cover UEFA because ‘it is technically a[n]

European organisation’ according to the approved legislative proposal[40]

and as interpreted by its initiator Roland Büchel MP.

As part of the future second package of Lex FIFA, Switzerland will implement legislation to make corruption

in sport a criminal offence. Insofar, private bribery (i.e. passive/active

bribery in the private sector) is only regarded as a criminal offence under

Article 4a and Article 23 of the Swiss Federal Unfair Competition Law following

a complaint.[41]

Conclusions

The lofty goals

of the Council of Europe’s report on reforming football’s governance are

laudable in principle, however they lack a clear reflection on the legal means

available to attain them. To this end, it is the main point of this blog post’s

author to attract the attention of the reader on the particular responsibility

of Switzerland in this regard. Due to FIFA and UEFA being legally seated in

Switzerland, Swiss law is tasked with the tough mission, in light of recent

events, to enforce via private law and

criminal law association governance standards on both non-profit organizations.

The future implementation of Lex FIFA

with regard to the criminalisation of corruption in sport, is a first step in

the right direction. What’s rather missing, however, is a private law

perspective. A comprehensive implementation of the report’s recommendations can

only be achieved if the interpretation of the relevant provisions of the Swiss

Code were to be in line with the report’s recommendations. Indeed, as a

prominent Council of Europe’ state party, Switzerland should be stricter when

assessing the (un)justifiability of a possible infringement by FIFA or UEFA of a

member’s rights under the Swiss notion of mandatory rules of law. In this

regard, it should also take into consideration the PACE report’s

recommendations on reforming the governance of football by FIFA and UEFA.

[1] E.g. Qatargate: la confession

accablante, France Football No. 3582, 9 December 2014, p. 19 et seq.

[2] Connarty, The

reform of football governance, PACE report, 27 January 2015, p. 17.

[3] Addink, Goed bestuur, Kluwer 2010, p. 6.

[4] ‘See OECD

Principles of Corporate Governance, 2004, p. 11, accessible at

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/32/18/31557724.pdf. ‘The EU corporate

governance framework includes legislation in areas such as corporate governance

statements, transparency of listed companies, shareholders’ rights and takeover

bids as well as ‘soft law’, namely recommendations on the role and on the

remuneration of companies’ directors.’

[5] COM 2012(740)

final, Action Plan: European company law and corporate governance - a modern

legal framework for more engaged shareholders and sustainable companies, p.

2-3.

[6] E.g., Giesen, Alternatieve regelgeving and

privaatrecht, Monografieën Privaatrecht, Kluwer 2007, p. 29.

[7] COM 2012(740)

final, Action Plan: European company law and corporate governance - a modern

legal framework for more engaged shareholders and sustainable companies, p. 3.

[8] COM 2012(740)

final, Action Plan: European company law and corporate governance - a modern

legal framework for more engaged shareholders and sustainable companies, p. 3.

[9] Valloni &

Pachmann, Sports law in Switzerland, Wolters Kluwer 2011, p. 65.

[10] Handschin, Good

governance: lessons for sports organizations?, in: Bernasconi, International

sports law and jurisprudence of the CAS, 2014, p. 118. Notes ommitted.

[11] Handschin, Good

governance: lessons for sports organizations?, in: Bernasconi, International

sports law and jurisprudence of the CAS, 2014, p. 118. Notes ommitted.

[12] Handschin, Good

governance: lessons for sports organizations?, in: Bernasconi, International

sports law and jurisprudence of the CAS, 2014, p. 119. Notes ommitted.

[13] Please do take into

account Weatherill’s statement on conditional autonomy of sports federations

under EU law: Weatherill, Is the Pyramid Compatible with EC Law?, ISLJ

2005(3–4), p. 3–7, republished in: Weatherill, European Sports Law Collected Papers Second

Edition 2014, available at: http://www.springer.com/law/international/book/978-90-6704-938-2.

[14] Valloni &

Pachmann, Sports law in Switzerland, Wolters Kluwer 2011, p. 40-44.

[15] Jakob, Huber and

Rauber, Nonprofit law in Switzerland, The Johns Hopkins comparative nonprofit

sector project, Working Paper No. 47, March 2009, p. 3, 5.

[16] Jakob, Huber and

Rauber, Nonprofit law in Switzerland, The Johns Hopkins comparative nonprofit sector

project, Working Paper No. 47, March 2009, p. 5.

[17] Pieth, Governing

FIFA – concept paper and report, 19 September 2011, p. 12. Tomlinson, FIFA

(Fédération Internationale de Football Association) : the men, the myths and

the money, 2014, p. 28.

[18] Pieth, Governing

FIFA – concept paper and report, 19 September 2011, p. 12.

[19] By the way, the EU-28 member

states are obliged to act in accordance with the Court of Justice rulings in, inter alia, Walrave (Case 36-74, ECR 1974

1405), Bosman (Case C-415/93, ECR

1995 I-4921) and

Meca Medina (Case C-519/04 P, ECR 2006 I-6991) with regard to the economic and rule-making

activities of UEFA and FIFA. For more information please see Weatherill, European Sports Law

Collected Papers Second Edition 2014, available at: http://www.springer.com/law/international/book/978-90-6704-938-2.

[20] Valloni &

Pachmann, Sports law in Switzerland, Wolters Kluwer 2011, p. 67-69.

[21] Article 1 FIFA

statutes; Article 1 UEFA statutes.

[22] Valloni &

Pachmann, Sports law in Switzerland, Wolters Kluwer 2011, p. 19, 40.

[23] Handschin, Good

governance: lessons for sports organizations?, in: Bernasconi, International

sports law and jurisprudence of the CAS, 2014, p. 126-127. Notes ommitted.

[24] Jakob, Huber and

Rauber, Nonprofit law in Switzerland, The Johns Hopkins comparative nonprofit

sector project, Working Paper No. 47, March 2009, p. 6.

[25] With the notable exception

of Article 75 CC.

[26] BGE 73 II 1.

[27] Jakob, Huber and

Rauber, Nonprofit law in Switzerland, The Johns Hopkins comparative nonprofit

sector project, Working Paper No. 47, March 2009, p. 6.

[28] Valloni &

Pachmann, Sports law in Switzerland, Wolters Kluwer 2011, p. 19.

[29] E.g., a dynamic

reference to accept the jurisdiction of the Court of Arbitration for Sports

(CAS).

[30] Morgan, The

relevance of Swiss law in doping disputes, in particular from the perspective

of personality rights – a view from abroad, in: Revue de droit suisse, Band 132

(2013) I Heft 3, p. 344-345. Fenners, Der ausschluss der staatlichen gerichtsbarkeit

in organisierten sport, Zurich 2006, paras. 111-113. Baddeley, L’Association

sportive face au droit – Les limites de son autonomie, Basel 1994, p. 108.

[31] Marco van der

Harst, Can (national or EU) public policy stop CAS awards?, 22 July 2014,

available at: http://www.asser.nl/SportsLaw/Blog/post/can-national-or-eu-public-policy-stop-cas-awards-by-marco-van-der-harst-ll-m-phd-candidate-and-researcher-at-the-aislc.

[32] BGE 97 II 108 et

seq. Valloni & Pachmann, Sports law in Switzerland, Wolters Kluwer 2011, p.

41.

[33] Let’s not forget

that there are two sports law cases pending versus Switzerland at the European

Court of Human Rights: Adrian Mutu (No. 40575/10) and Claudia Pechstein (No.

67474/10).

[34] Morgan, The

relevance of Swiss law in doping disputes, in particualr from the perspective

of personality rights – a view from abroad, in: Revue de droit suisse, Band 132

(2013) I Heft 3, p. 344, note 6: Decision 4A_558/2011 of 27 March 2012; ATF 134

III 193 (Further notes omitted).

[35] E.g., Morgan, The

relevance of Swiss law in doping disputes, in particualr from the perspective

of personality rights – a view from abroad, in: Revue de droit suisse, Band 132

(2013) I Heft 3, p. 344-345.

[36] E.g., Morgan, The

relevance of Swiss law in doping disputes, in particualr from the perspective

of personality rights – a view from abroad, in: Revue de droit suisse, Band 132

(2013) I Heft 3, p. 344-345.

[37] Deadline: April 2,

2015. Source: http://www.admin.ch/opc/de/federal-gazette/2014/9689.pdf.

[38] In order to prevent being blacklisted by the Organisation for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD), Switzerland had to implement the 2012

Recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) with regard to

combating money laundering and terrorist financing.

[39] Sources: http://www.sportsintegrityinitiative.com/swiss-law-requires-bank-account-monitoring-sports-federation-heads/ and http://www.rolandbuechel.ch/news_850_lex-fifa-interessiert-auch-die-russen-buechel-auf-den-russischen-sputnik-news.xhtml.

[40] Bundesgesetz zur Umsetzung der

2012 revidierten Empfehlungen der Groupe d’action financière, December 12, 2014,

p. 9697-9698. Available at: http://www.admin.ch/opc/de/federal-gazette/2014/9689.pdf.

[41] Cassini, Corporate

responsibility and compliance programs in Switzerland, in: Manacorda, Centonze

and Forti (eds.), Preventing corporate corruption: the anti-bribery compliance

model, Springer 2014, p. 493.