The first part of our “Unpacking Doyen’s TPO deals” blog series concerns

the agreements signed between Doyen Sports and the Dutch football club FC

Twente. In particular we focus on the so-called Economic Rights Participation Agreement (ERPA) of 25 February 2014. Based on the ERPA we will be able to better

assess how TPO works in practice. To do so, however, it is necessary to explore

FC Twente’s rationale behind recourse to third-party funding. Thus, we will

first provide a short introduction to the recent history of the club and its

precarious financial situation.

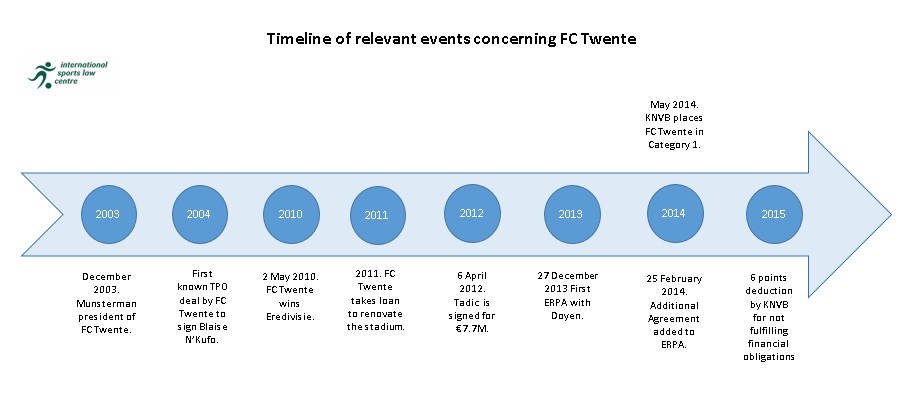

I. FC Twente 2004-2015

When local millionaire Joop Munsterman took over FC Twente in December 2003,

the club was on the verge of bankruptcy. Munsterman certainly did not lack ambition

and wanted to turn FC Twente into the best club of the Netherlands. With help

of external investors, he quickly managed to reinforce the team with quality players

such as the Swiss international Blaise N’kufo, the man who would later become FC Twente’s

all-time top scorer. A few years later, in 2010, FC Twente won the Dutch League

(Eredivisie), thereby defying the decade long dominance of Ajax, PSV and

Feyenoord. By now the club was considered an example for a modern, innovative

and successful football governance, and an inspiration for other smaller clubs.

Through “excellent scouting” it managed to attract players from all over the

world capable of winning the league and securing a spot in Europe’s most

important and lucrative club competition, the UEFA Champions League. Moreover,

Twente’s success on the field also led to financial success off the field. For

example, Costa Rican international Bryan Ruiz was signed from KAA Gent in 2009 for €5

million and sold to Fulham in 2011 for €12.5 million, which makes for a healthy

profit of €7.5 million.

The taste of the 2010 success and the additional earnings for

participating in the Champions League created hunger for more. The club started

spending large amounts of money on the transfer market, including the signings

of Leroy Fer in 2011 for €5.5 million and Dusan Tadic in 2012 for €7.7 million. Furthermore, with

the ambition of playing the Champions League consistently, the club decided to

renovate and expand its stadium. Although FC Twente is the owner of the

stadium, it did not have the means to finance the renovation. Therefore, it had

recourse to external investors, including the municipality of Enschede, who

provided a loan of €20 million.

Fast-forwarding to 2015, little is left of that over-ambitious FC

Twente. The club currently finds itself in the lower ranks of the league table

and is fearing relegation to the second league. Much-needed revenue from

Champions League participation did not materialize since the club was not able

to qualify after 2011 and many of the recent signings did not lead to transfer

profits. In May 2014 the Dutch FA, KNVB, placed FC Twente into the so-called “Category 1”, a

category dedicated to clubs in financial difficulties, which could face

disciplinary sanctions if the financial situation is not improved swiftly.[1] In

early 2014, FC Twente had probably taken on way too much financial risk and was

in dire need of fresh money. In this context, the ERPA with Doyen was dearly

needed to repay outstanding short-term debts.

Timeline.jpg (64KB)

II. The ERPA dissected

The ERPA between FC Twente and Doyen Sports is dated from 25 February

2014. The ERPA consists of two separate agreements: a first general agreement

signed on 27 December 2013; and a second agreement added on 25 February 2014.

By means of the ERPA, Doyen purchased part of the economic rights of seven players

who at the time were all registered and playing for FC Twente, namely Castaignos,

Promes, Ould Chikh, Mokhtar, Eghan, Ebecilio and Tadic. In return, Doyen

provided FC Twente a fee for each of the players for a total amount of €5

million.

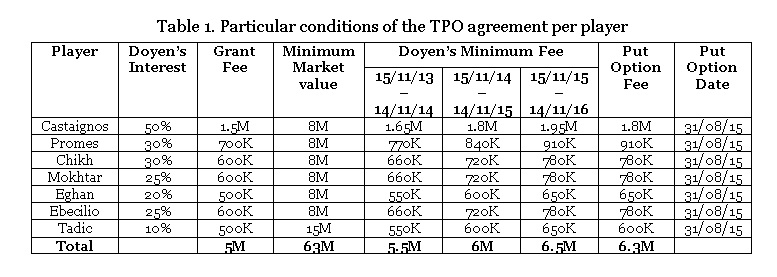

As stated, Doyen did not obtain all of the economic rights of the players,

but only a share. The share acquired by Doyen varied from player to player and

fluctuated between 10% (for Tadic) and 50% (for Castaignos). At first glance,

the mechanism seems relatively straightforward: once a player is sold to

another football club Doyen receives an amount equal to its share of the

economic rights attached to the player. However, the story is a bit more

complex. The ERPA provides for a minimum fee per player that is superior to the

amount Doyen invested in that player. In other words, regardless of the

transfer fee paid, Doyen will always make a profit. The bank always wins! Doyen’s

minimum fee for each player has been set at a basic amount equivalent to the fee

granted to FC Twente plus a fixed 10% to be increased at an annual rate of 10%

elapsed as from 15 November 2013.

The ERPA further sets out different scenarios which are described below.

A. Scenario

1&2: The Transfer offer

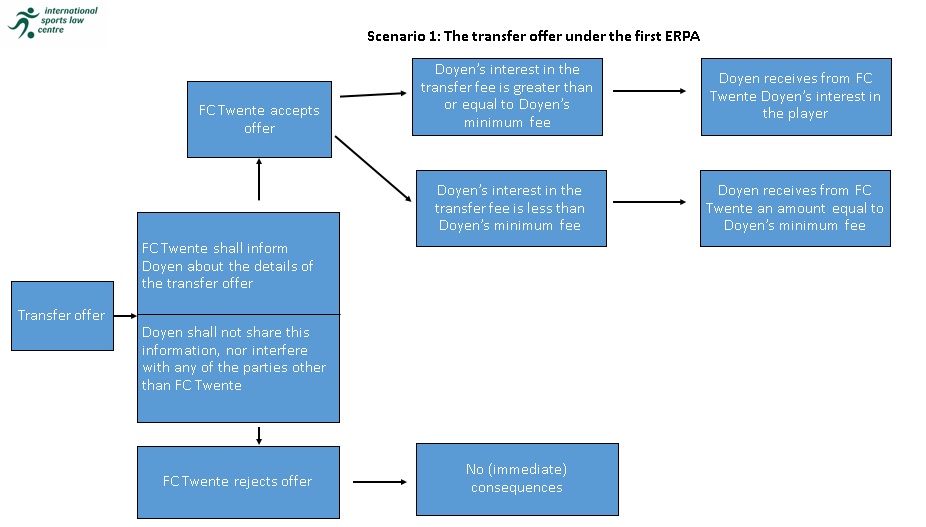

The first eventuality, and most likely the mutually desired one, is the

transfer of the player. Under the first agreement (this part was central to its

amendment), in case of a transfer offer for one of the players concerned by the

agreement, FC Twente could choose to accept or reject the offer. If it accepted

the offer, Doyen was entitled to the agreed share of the proceeds of the

transfer. If this amount was inferior to Doyen’s minimum fee, then Twente had

to pay the fee. In case Twente would refuse the offer, no further contractual

consequences were foreseen. (Scenario 1). It appears from the latest release of

footballleaks (available here) that the first agreement actually entailed a different scenario, which

was later deleted from the ERPA and inserted in an additional agreement. This

second agreement, added later to the ERPA and not communicated to the KNVB,

radically changed the transfer scenario (Scenario 2).

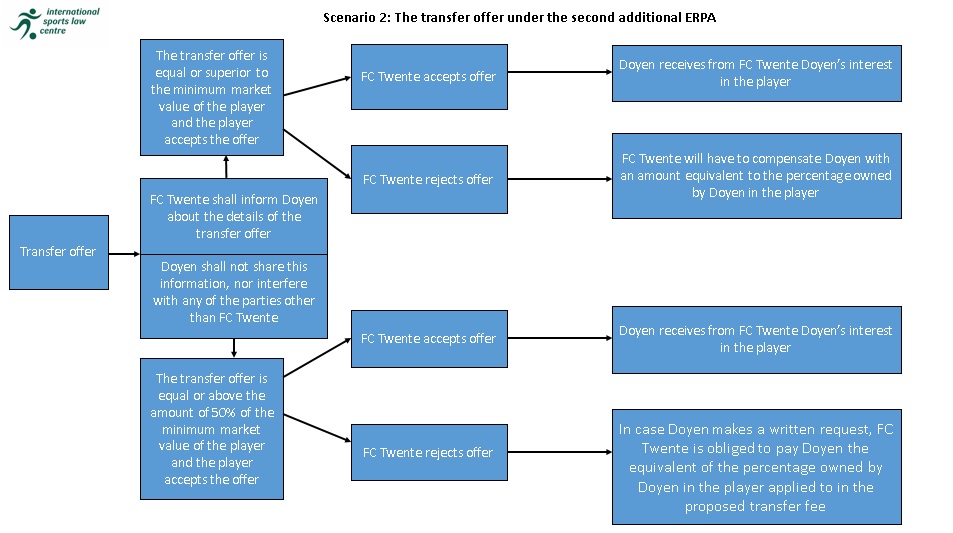

Under the second agreement, in case of a transfer offer equal or

superior to the minimum market value of the player is received and rejected by

the club, FC Twente is obliged to compensate Doyen by an amount equivalent to Doyen’s

share of the proposed transfer fee. By way of illustration, say a given

football club offers FC Twente €10 million for Castaignos, while his minimum market

value is €8 million (see table 1). Should FC Twente reject this transfer offer

it will be obliged to compensate Doyen for an amount of €5 million (50% of the

proposed transfer fee of €10 million). Similarly, if the proposed transfer fee

is equal or above 50% of the minimum market value and FC Twente rejects it, it

could also be obliged to compensate Doyen. Using Castaignos again as an

example, say the proposed transfer fee was not €10 million but €4 million. This

amount is exactly 50% of Castaignos’ minimum market value. Should FC Twente

decide to reject this offer and Doyen decides to make a written request to be

compensated, Doyen could claim €2 million from FC Twente.

Scenario1.jpg (85.9KB)

Scenario2.jpg (119.7KB)

B. Scenario

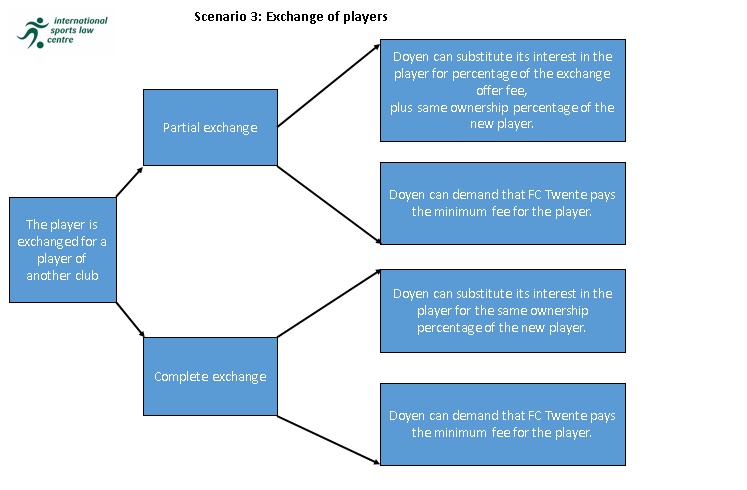

3: Exchange of players

If Twente decides to exchange a player covered by the ERPA against

another player, to which an additional fee might be added, the agreement

foresees that Doyen will have three different options. First, Doyen can, in

case of a partial exchange involving a complementary fee, decide to keep the

same share of the economic rights attached to the new player and get the agreed

share of the fee received by the club. If a one-to-one exchange takes place,

Doyen can only keep the same share of the economic rights attached to the new

player. Finally, in both types of exchanges, Doyen has the option to demand

that FC Twente pays the minimum fee for the player.

Scenario3.jpg (67.3KB)

C. Scenario

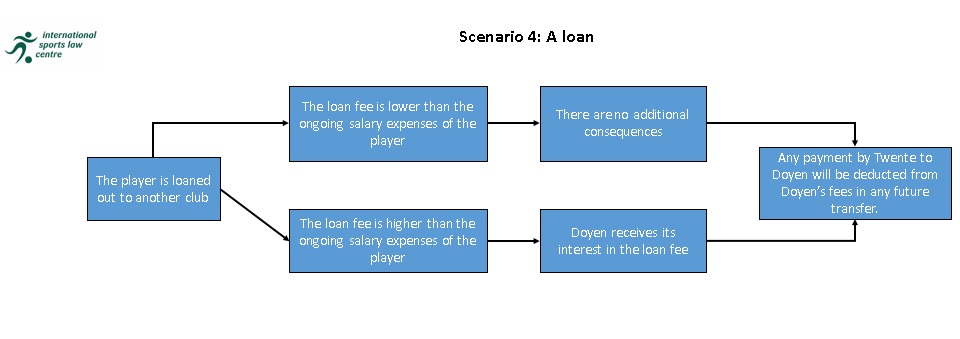

4: A loan

In the third scenario, the player is loaned out to another club. If the

loan fee received is higher than the wage bill of the player at FC Twente, the

club makes a profit on the loan. Consequently, Doyen is entitled to receive a

percentage of the loan fee. Doyen’s share of the loan fee is calculated on the

basis of its share in the economic rights of the player concerned. If

Castaignos were to be loaned out to another club and FC Twente receives a loan

fee higher than its salary, Doyen would receive 50% of the profit on the loan

fee.

Scenario4.jpg (51.1KB)

D. Scenario

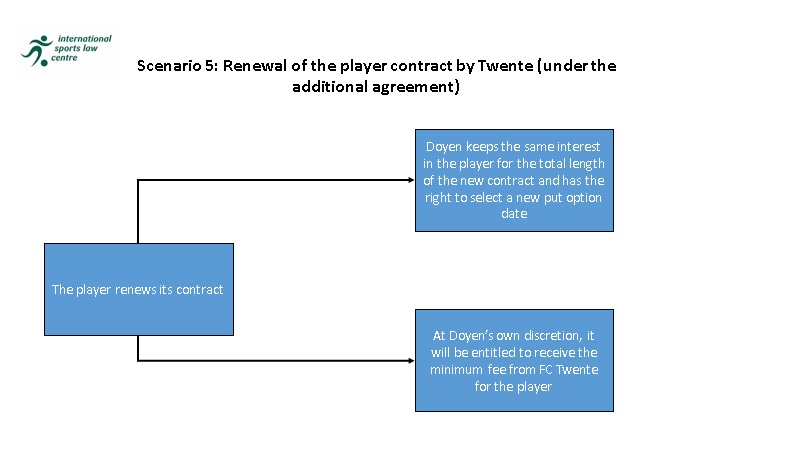

5: Renewal of the player contract by Twente

The fourth scenario is also modified

by the additional agreement signed on 25 February 2014. Under the original

agreement, if the player renews his contract with FC Twente, Doyen simply keeps

the same share of the economic rights for the total length of the new contract.

However, Doyen does have the right to choose a new put option date or, importantly,

simply stick to the old put option date (on the put option date see below

scenario 6). Under the additional agreement, Doyen also has the possibility to

request that the minimum fee be paid by FC Twente.

Scenario5.jpg (47.7KB)

E. Scenario

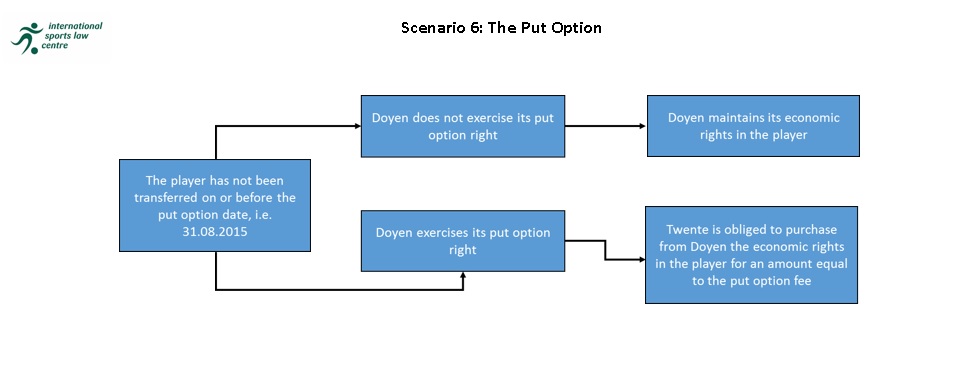

6: The Put Option

In the ERPA, Doyen and FC

Twente have agreed a put option, this alternative is covered in Scenario 5. A

put option is a right given to Doyen to sell back its share of the economic

rights linked to a player at FC Twente, at a given date and for a given price.

The put option date was set at 31 August 2015 for all seven players of

Twente(see table 1). To use a concrete example, Ebecilio was not sold before 31

August 2015. In fact, he currently still plays for FC Twente. In accordance

with the particular conditions of the ERPA, Doyen had the right to sell to FC

Twente its share of the economic rights of Ebecilio, and FC Twente would have

the obligation to buy back those rights, for a fixed put option fee. According

to Table 1, the put option fee for Ebecilio is €780.000. Whether Doyen actually

exercised this option in the Ebecilio case is not clear, but it would have

guaranteed the investment company a profit of €180.000.

Scenario6.jpg (48.6KB)

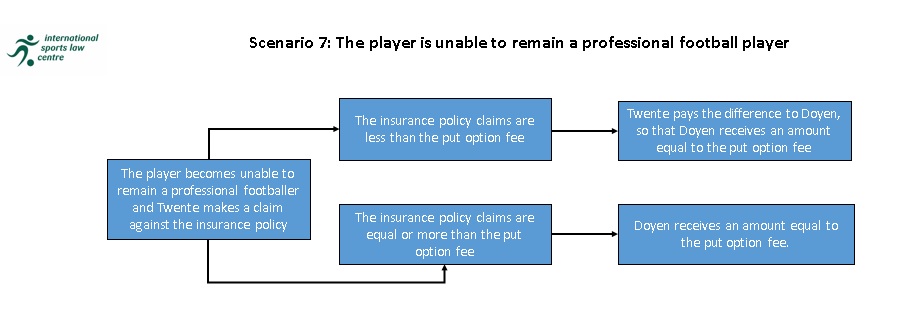

F. Scenario

7: The player is unable to remain a professional football player

Point 8 of the ERPA foresees that FC Twente shall enter into a policy

with an insurance company insuring the risk of the player’s death and the risk

of the player suffering an incapacitating injury or any injury which may

patently reduce the player’s ability as a professional football player. In the

case of such events, Doyen will receive an amount equal to the put option fee,

irrespective of whether the insurance policy claims are lower or higher than

the put option fee.

Scenario7.jpg (55.5KB)

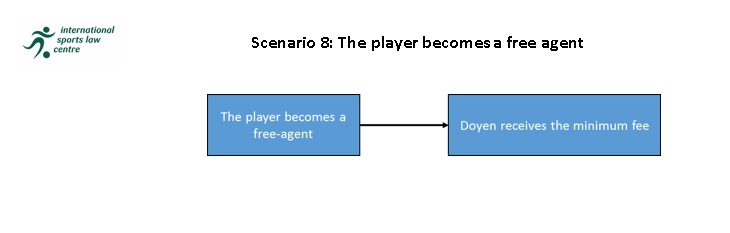

G. Scenario 8: The player becomes a free agent

Point 9.1 of the ERPA stipulates that FC Twente “shall use its best

endeavors to prevent the Player from becoming a free agent and acknowledges

that such endeavors are considered normal and ordinary business practice for

professional football clubs”. The notion of “best endeavors” remains undefined

and mysterious. Nonetheless, in the case a player’s contract expires and he

becomes a free agent, FC Twente will be obliged to pay Doyen the minimum fee agreed

in the particular conditions (see table 1).

Scenario8.jpg (18.4KB)

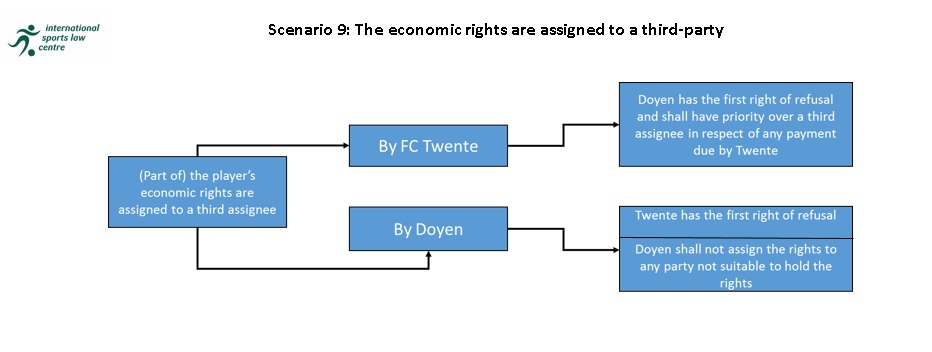

H. Scenario 9: The economic rights are assigned to

a third-party

After the signature of the ERPA, it is still possible to trade the economic

rights attached to the same players with third parties. However, if Doyen

wishes to sell the economic rights of one of the seven players, it would

firstly have to offer those rights back to FC Twente on the same conditions as

those that would be offered to third parties. Moreover, Doyen may not assign

any share of the players’ economic rights to any Dutch club or to any other

third party which is not suitable to hold them. In turn, should FC Twente wish

to sell (part of) the remaining economic rights of a player, it would firstly

have to offer these rights to Doyen before offering them to another assignee.

Scenario9.jpg (51.1KB)

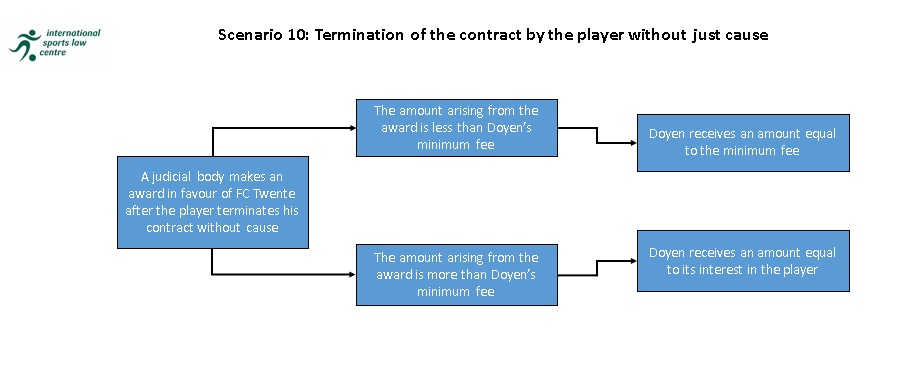

I. Scenario

10: Termination of the contract by the player without just cause

Final scenario, if the player terminates his contract without just cause

(see Article 17 FIFA RSTP), the ERPA foresees that FC Twente shall

pursue a claim for unlawful termination of the employment contract against the

player before any competent judicial institution.[2]

If the relevant judicial body grants compensation to FC Twente, Doyen will get

a share of the compensation equivalent to its share of the economic rights of

the player. In the event the share of the compensation awarded to Doyen is less

than the minimum fee, FC Twente will have to match the minimum fee.

Scenario10.jpg (54.2KB)

III. The aftermath of the ERPA

On 26 November 2015, FC Twente told the Dutch press that it had bought off the TPO

contract with Doyen. On that same day, footballleaks

published a Settlement Agreement between Doyen and FC Twente. According to this

settlement, the parties agreed to terminate the ERPA on the condition that

Twente would pay to Doyen a compensation of €3.344.519. Whether the settlement

agreement was signed by the two parties remains unknown since it does not

include a date nor any signatures.

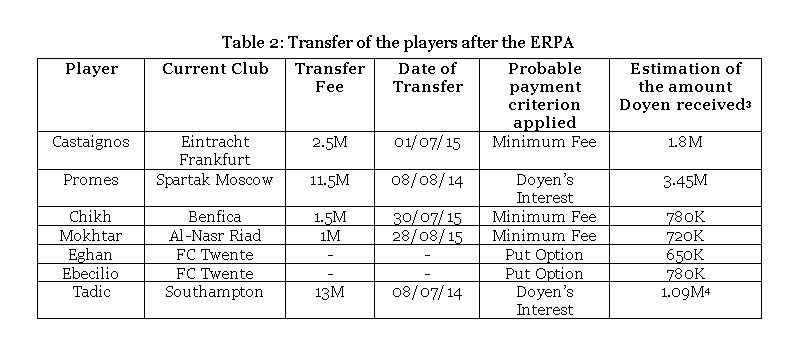

What is known is what happened to the seven players whose economic rights

were partly sold to Doyen. Based on the information provided by the German

website http://www.transfermarkt.de/, we made the following table summarizing the

situation:

Since the signing of the ERPA (27 December 2013), five players have been

transferred to other football clubs and two (Eghan and Ebecilio) are still

under contract at FC Twente. Two players, Tadic and Promes, were sold for a

relatively high fee (€13 million and €11.4 million respectively). For Tadic’s

transfer, it is known that Doyen received a 10% of the transfer, since the fee

was higher than the minimum fee. In fact, footballleaks

provides a document called “Liquidation of Economic Rights Participation - Tadic”, holding that Doyen received €1.091.250 from

Tadic’s €13 million transfer to English side Southampton. Doyen’s interest in

Tadic was 10%. In principle this would mean that Doyen would receive 10% of €13

million, i.e. €1.3 million. However, based on article 7.2. of the ERPA, agent fees,

solidarity contributions and the claim of another club (Groningen) were deducted

to arrive at the final figure. The same process will have applied to the

transfer of Promes.

Castaignos, Chikh and Mokhtar were sold for relatively low transfer fees

(€2.5 million, €1.5 million and €1 million respectively). It is now possible to

predict what truly happened to Doyen’s share of Castaignos’ economic rights. As

Doyen’s share of the economic rights attached to Castaignos was 50% (see table

1), it should get €1.25 million (50% of €2.5 million). However, the particular conditions

also stipulate that in such a case Doyen would be awarded the minimum fee, on 1

July 2015 it amounted to €1.8 million. Because Doyen’s share of Castaignos’

transfer fee (€1.25 million) is lower than the minimum fee (€1.8 million), it probably

received the latter.

As to Ebecilio and Eghan, both remained at FC Twente after the put option

date passed (31 August 2015), whether Doyen exercised its put option or not

remains unknown. If Doyen has exercised this option, it would have received

€780.000 for Ebecilio and €650.000 for Eghan.

Typically, these fees are not paid immediately at the date of the transfer.

Instead the payment is divided in separate instalments. It is possible (even

likely in light of its price tag), but we lack definite information on this

point, that the settlement agreement between Doyen and FC Twente covers all

outstanding instalments regarding previous transfers.

IV. Is the ERPA in breach of KNVB and FIFA

Regulations?

The Dutch media is full of rumours about the

terrible things that are about to happen to FC Twente. Is the club going to go

bankrupt? Or, will it be “only” losing more points in an already difficult

battle to save its place in the Eredivisie? Until now, with few exceptions,

very little substantial legal analysis has been provided. The KNVB and FIFA are

the two main private regulators susceptible of going after FC Twente, though

UEFA has also been mentioned in the press, but we are unable to identify under which

legal basis it could get involved in the matter. One thing is certain, entering

an ERPA with Doyen is a losing bet for a club. It takes huge financial risks and

is the only actor facing disciplinary sanctions as Doyen escapes the

jurisdiction of the football associations.

A. Has FC Twente breached the rules of the KNVB?

Pursuant to Article 57(1) of the KNVB Regulations, it is prohibited for clubs to reach any

agreement that allows a third party to influence the club’s independence

regarding the transfers of players. This provision is a mandatory transposition

by the Dutch FA, as provided by article 1.3 of the FIFA Regulations on the

Status and Transfer of Players (RSTP), of article 18bis RSTP (See below). The

KNVB has stated that it was aware of the existence of the ERPA

between FC Twente and Doyen and that it even intervened to prevent unauthorized

influence by Doyen. However, the Dutch FA was apparently not informed of the

existence of the additional agreement signed between Doyen and FC Twente and a

KNVB insider was quoted saying that those provisions “appear to show that Doyen does exert

influence on FC Twente”.

Yet, at the time of writing, it remains unclear whether FC Twente is subjected

to a formal investigation by the KNVB.

In fact, the difference between the original

agreement and the additional agreement is flagrant and crucial. In the former

case FC Twente was entirely free to refuse a transfer offer whatever its

amount, while, in the latter, if an offer reached a minimum amount, the club

was forced to sell the player or to pay out Doyen’s share on the offer. At this

point in time, all parties must have been perfectly conscious that FC Twente

was unable to disburse any cent to buy back the economic rights owned by Doyen.

Hence, its transfer policy was entirely at the goodwill of the investment fund

and the potential buyers. The fact that FC Twente did not disclose the

additional agreement to the KNVB obviously vindicates this assessment. Moreover,

the latest release by footballleaks

shows that the original ERPA signed in December 2013 included some of the

most controversial provisions regarding transfers. These were later redacted

out of the agreement and inserted in the additional agreement, probably to

circumvent the control of the KNVB. It will be extremely difficult for the KNVB

to deny that Doyen exercised a substantial influence on FC Twente’s transfer

decisions regarding the players subjected to the ERPA. The potential sanctions

are listed in Article 11 of the License Regulations (page 78-90 of the KNVB

Regulations) and include a fine, a points deduction or withdrawal of the

license. Having in mind the severe financial situation FC Twente finds itself

in, this could lead to the full-blown bankruptcy of the club.

B. Has FC Twente breached the FIFA Regulations?

FC Twente might be facing a FIFA sanction as

well. As everybody knows by now, the FIFA ban on TPO entered into force on 1

May 2015.[3] However,

the ERPA between FC Twente and Doyen is not falling under the ban, as it is not

applicable retroactively. Hence, its conformity to FIFA regulations can only be

assessed in relation to the FIFA Regulations on the Status and

Transfer of Players

(RSTP) in force at the signature of the ERPA. Back then article 18bis of the

RSTP on third-party influence on clubs provided that:

1.

No club shall enter into a contract which enables any other party to

that contract or any third party to acquire the ability to influence in

employment and transfer-related matters its independence, its policies or the

performance of its teams.

2.

The FIFA Disciplinary Committee may impose disciplinary measures on

clubs that do not observe the obligations set out in this article.

The whole legal debate will hinge, as for KNVB

proceedings, on whether Doyen had the ability to influence the policy of FC

Twente in employment and transfer-related matters. As we have argued above, the

agreement points a loaded financial gun at FC Twente’s head each time a

transfer offer of a certain amount is made, or when the club wishes to renew

the contract of a player subjected to the ERPA. There is very little doubt that

the transfer policy of a club in financial difficulties will be directly

influenced by an investor, which can financially pull the plug on the club at

virtually any time if it refuses to sell a player for a certain fee. The

problem now for FIFA (and KNVB) will be to find an appropriate sanction for the

club. It is the only party facing disciplinary proceedings (Doyen is out of

FIFA or KNVB’s disciplinary reach). In the end, the supporters and players are

the victims of a gross mismanagement of the club’s affairs due to the hubris of

an irresponsible president. FIFA will also have to decide whether the many other

ERPAs signed by Doyen (you can find a probably incomplete list of Doyen’s

investment in players here), which include similar provisions (see Doyen’s model ERPA here) are also in breach of article 18bis. If yes, and we think there is no

reason to decide otherwise, then a number of clubs (think Atletico, Sporting or

Porto) might face FIFA (or national FA)

sanctions in the near future. This case is not ending with FC Twente, it is

about all the clubs that have signed an ERPA with Doyen Sport in the past.

Additionally, it is also possible that FC

Twente be found in breach of Annexe 3 of the FIFA RSTP, which regulates the use

of the FIFA ‘Transfer Matching System’ (TMS) in the case of a transfer. The TMS is

an online system that intends to make international transfers of players

between clubs quicker, smoother and more transparent. Under article 4.4 of

Annexe 3, in case FC Twente transfers a player (five of the players concerned

by the ERPA have been transferred), it must introduce in the FIFA TMS a ‘Declaration on third-party payments

and influence’. It is thinkable that FC Twente did not include the full ERPA in

the TMS system and might also, therefore, face the FIFA sanctions provided in

article 9.4 of the Annexe.

In a nutshell, FC Twente is now in deep(er) trouble because it decided

to play Maltese roulette with a ruthless investor.

[1] In fact, the KNVB has already deducted six

points from FC Twente in the 2014/15 season for financial mismanagement.

[2] Point 9.4 of the ERPA.

[3] More information on the TPO

ban can be found in our previous Bogs, such as “Blog Symposium:

FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law – Introduction”.