Introduction: FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law.

Day 1: FIFA must regulate TPO, not ban it.

Day 2: Third-party entitlement to shares of transfer fees: problems and solutions

Day 3: The Impact of the TPO Ban on South American Football.

Day 5: Why FIFA's TPO ban is justified.

Editor's note: In this fourth part of our blog symposium on FIFA's TPO ban Daniel Geey shares his 'UK perspective' on the ban. The English Premier League being one of the first leagues to have outlawed TPO in 2010, Daniel will outline the regulatory steps taken to do so and critically assess them. Daniel is an associate in Field Fisher Waterhouse LLP's Competition and EU Regulatory Law Group. As well as being a famous 'football law' twitterer, he has also published numerous articles and blogs on the subject.

What is

Third Party Investment?

In brief

Third Party Investment (TPI) in the football industry, is where a football club

does not own, or is not entitled to, 100% of the future transfer value of a

player that is registered to play for that team. There are numerous models for

third party player agreements but the basic premise is that companies,

businesses and/or individuals provide football clubs or players with money in

return for owning a percentage of a player’s future transfer value. This

transfer value is also commonly referred to as a player’s economic rights.

There are instances where entities will act as speculators by purchasing a

percentage share in a player directly from a club in return for a lump sum that

the club can then use as it wishes. More...

Introduction: FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law.

Day 1: FIFA must regulate TPO, not ban it.

Day 2: Third-party entitlement to shares of transfer fees: problems and solutions

Day 4: Third Party Investment from a UK Perspective.

Day 5: Why FIFA's TPO ban is justified.

Editor’s note: Ariel N. Reck is an Argentine

lawyer specialized in the football industry. He is a guest professor at ISDE’s

Global Executive Master in International Sports Law, at the FIFA CIES Sports

law & Management course (Universidad Católica Argentina) and the Universidad

Austral Sports Law diploma (Argentina) among other prestigious courses. He is a

regular conference speaker and author in the field of sports law.

Being an Argentine lawyer, Ariel will focus on the impact FIFA’s TPO ban

will have (and is already having) on South American football.More...

Introduction: FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law.

Day 1: FIFA must regulate TPO, not ban it.

Day 3: The Impact of the TPO Ban on South American Football.

Day 4: Third Party Investment from a UK Perspective.

Day 5: Why FIFA's TPO ban is justified.

Editor’s note: Raffaele

Poli is a human geographer. Since 2002, he has studied the labour and transfer

markets of football players. Within the context of his PhD thesis

on the transfer networks of African footballers, he set up the CIES Football Observatory based

at the International Centre for Sports Studies (CIES) located in Neuchâtel,

Switzerland. Since 2005, this research group

develops original research in the area of football from a multidisciplinary

perspective combining quantitative and qualitative methods. Raffaele was also involved in a recent study on TPO providing FIFA with more background information on its functioning and regulation (the executive summary is available here).

This is the third blog of our Symposium

on FIFA’s TPO ban, it is meant to provide an interdisciplinary view on the

question. Therefore, it will venture beyond the purely legal aspects of the ban

to introduce its social, political and economical context and the related

challenges it faces. More...

Introduction: FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law.

Day 2: Third-party entitlement to shares of transfer fees: problems and solutions

Day 3: The Impact of the TPO Ban on South American Football.

Day 4: Third Party Investment from a UK Perspective.

Day 5: Why FIFA's TPO ban is justified.

Editor's note: This is the first blog of our symposium on FIFA's TPO ban, it features the position of La Liga regarding the ban and especially highlights some alternative regulatory measures it would favour. La Liga has launched a complaint in front of the European Commission challenging the compatibility of the ban with EU law, its ability to show that realistic less restrictive alternatives were available is key to winning this challenge. We wish to thank La Liga for sharing its legal (and political) analysis of FIFA's TPO ban with us.

INTRODUCTION

The Spanish Football League (La Liga) has argued for months that the funding of clubs through the conveyance of part of players' economic rights (TPO) is a useful practice for clubs. However, it also recognized that the

practice must be strictly regulated. In July 2014, it approved a provisional regulation that was sent to many of the relevant stakeholders, including FIFA’s Legal Affairs Department. More...

Day 1: FIFA must regulate TPO, not ban it.

Day 2: Third-party entitlement to shares of transfer fees: problems and solutions

Day 3: The Impact of the TPO Ban on South American Football.

Day 4: Third Party Investment from a UK Perspective.

Day 5: Why FIFA's TPO ban is justified.

On

22 December 2014, FIFA officially introduced

an amendment to its Regulations on the Status and Transfers of Players banning third-party ownership of players’

economic rights (TPO) in football. This decision to put a definitive end to the

use of TPO in football is controversial, especially in countries where

TPO is a mainstream financing mechanism for clubs, and has led the Portuguese

and Spanish football leagues to launch a complaint in front of the European

Commission, asking it to find the FIFA ban contrary to EU competition law.

Next week, we will feature a Blog Symposium

discussing the FIFA TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law. We

are proud and honoured to welcome contributions from both the complainant (the

Spanish football league, La Liga) and the defendant (FIFA) and three renowned

experts on TPO matters: Daniel Geey ( Competition lawyer at Fieldfisher, aka @FootballLaw), Ariel Reck (lawyer at

Reck Sports law in Argentina, aka @arielreck)

and Raffaele Poli (Social scientist and head of the CIES Football Observatory). The

contributions will focus on different aspects of the functioning of TPO and on

the impact and consequences of the ban. More...

On 21 January 2015, the Court of

arbitration for sport (CAS) rendered its award in the latest avatar of the Mutu case, aka THE sports law case that

keeps on giving (this decision might still be appealed to the Swiss Federal

tribunal and a complaint by Mutu is still pending in front of the European

Court of Human Right). The decision was finally published on the CAS website on

Tuesday. Basically, the core question focuses on the interpretation of Article

14. 3 of the FIFA Regulations on the Status and

Transfer of Players in its 2001 version. More precisely, whether, in case of a dismissal of a player

(Mutu) due to a breach of the contract without just cause by the

player, the new club (Juventus and/or Livorno) bears the duty to pay the

compensation due by the player to his former club (Chelsea). Despite winning maybe

the most high profile case in the history of the CAS, Chelsea has been desperately

hunting for its money since the rendering of the award (as far as the US), but

it is a daunting task. Thus, the English football club had the idea to turn

against Mutu’s first employers after his dismissal in 2005, Juventus and

Livorno, with success in front of the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber (DRC),

but as we will see the CAS decided otherwise[1]. More...

The world of professional cycling and doping have been closely intertwined

for many years. Cycling’s International governing Body, Union Cycliste

Internationale (UCI), is currently trying to clean up the image of the sport

and strengthen its credibility. In order to achieve this goal, in January 2014

the UCI established the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC) “to conduct a wide ranging independent investigation

into the causes of the pattern of doping that developed within cycling and allegations

which implicate the UCI and other governing bodies and officials over

ineffective investigation of such doping practices.”[1] The final report was submitted to the

UCI President on 26 February 2015 and published on the UCI website on 9 March 2015. The report

outlines the history of the relationship between cycling and doping throughout

the years. Furthermore, it scrutinizes the role of the UCI during the years in

which doping usage was at its maximum and addresses the allegations made

against the UCI, including allegations of corruption, bad governance, as well

as failure to apply or enforce its own anti-doping rules. Finally, the report turns

to the state of doping in cycling today, before listing some of the key practical

recommendations.[2]

Since the day of publication, articles and commentaries (here and here) on the report have been burgeoning and many

of the stakeholders have expressed their views (here and here). However, given the fact that the report is

over 200 pages long, commentators could only focus on a limited number of

aspects of the report, or only take into account the position of a few

stakeholders. In the following two blogs we will try to give a comprehensive

overview of the report in a synthetic fashion.

This first blogpost will focus on the relevant findings and

recommendations of the report. In continuation, a second blogpost will address

the reforms engaged by the UCI and other long and short term consequences the

report could have on professional cycling. Will the recommendations lead to a

different governing structure within the UCI, or will the report fundamentally

change the way the UCI and other sport governing bodies deal with the doping

problem? More...

It took only days for the de facto immunity of the Court of

Arbitration for Sport (CAS) awards from State court interference to collapse

like a house of cards on the grounds

of the public policy exception mandated under Article V(2)(b) of the New York Convention on the Recognition and

Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards . On 15 January 2015, the

Munich Court of Appeals signalled an unprecedented turn in the

longstanding legal dispute between the German speed skater, Claudia Pechstein,

and the International Skating Union (ISU). It refused to recognise a CAS

arbitral award, confirming the validity of a doping ban, on the grounds that it

violated a core principle of German cartel law which forms part of the German public

policy. A few weeks before, namely on 30 December 2014, the Court of Appeal of Bremen held a CAS award, which ordered the German Club, SV Wilhelmshaven, to

pay ‘training compensation’, unenforceable for non-compliance with mandatory

European Union law and, thereby, for violation of German ordre public. More...

'Can't fight corruption with con tricks

They use the law to commit crime

And I dread, dread to think what the future

will bring

When we're living in gangster time'

The Specials - Gangsters

The pressing need for change

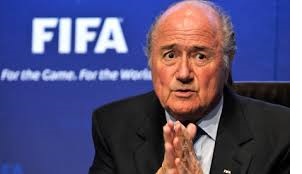

The

Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) of the Council of Europe (CoE), which is composed

of 318 MPs chosen from the national parliaments of the 47 CoE member states,

unanimously adopted a report entitled ‘the reform of

football’

on January 27, 2015. A draft resolution on the report will be debated during the

PACE April 2015 session and, interestingly, (only?) FIFA’s president Sepp

Blatter has been sent an invitation.

The PACE report

highlights the pressing need of reforming the governance

of football by FIFA and UEFA respectively. Accordingly, the report contains

some interesting recommendations to improve FIFA’s (e.g., Qatargate[1]) and

UEFA’s governance (e.g., gender representation). Unfortunately, it remains unclear

how the report’s recommendations will actually be implemented and enforced.

The report is a

welcomed secondary effect of the recent Qatargate directly involving former

FIFA officials such as Jack Warner, Chuck Blazer, and Mohamed Bin Hammam[2] and

highlighting the dramatic failures of FIFA’s governance in putting its house in

order. Thus, it is undeniably time to correct the governance of football by FIFA

and its confederate member UEFA – nolens

volens. The real question is how to do it.

Photograph:

Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images Photograph:

Octav Ganea/AP

More...