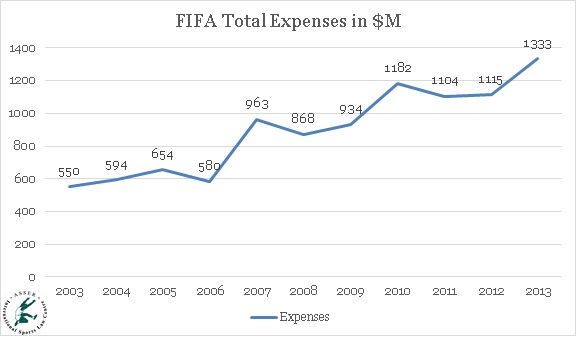

Our first report on the FIFA business dealt with FIFA’s revenues and highlighted

their impressive rise and progressive diversification. In parallel to this

growth of FIFA’s income, it is quite natural that its expenses have been

following a similar path (see Graph 1). However, as we will see FIFA makes it

sometimes very difficult to identify precisely where the money is going. Nonetheless,

this is precisely what we wish to tackle in this post, and to do so we

will rely on the FIFA Financial reports over the last 10 years.

Graph 1: FIFA Expenses in USD million (adjusted for inflation),

2003-2013.

The question of the final destination of FIFA’s money is a contentious

one. Many allege that FIFA executives may be profiting directly or indirectly

from the revenues amassed. In order to better understand to what end

FIFA’s money is disbursed, we have gathered the data contained in FIFA’s

Financial Reports over a 10 year time frame and we have adjusted the numbers

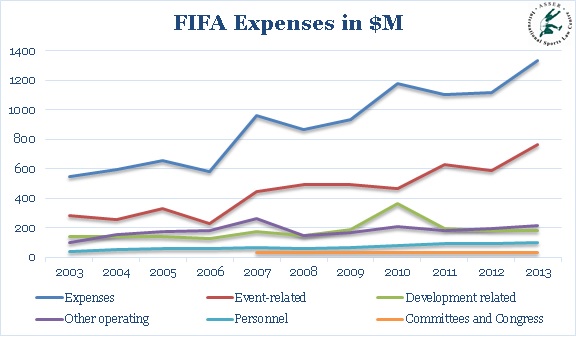

for inflation, thus easing any comparison. This data is synthetized in Graphs 2

and 3.

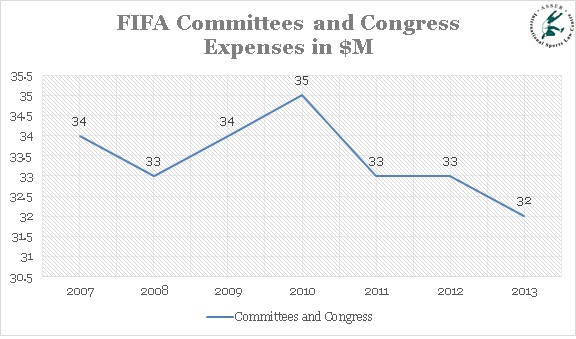

Graph 2 provides a comparative overview of the evolution of the expenses

of FIFA in absolute numbers. This shows that event-related and personnel

expenses (to a lesser extent also other operating costs) have been rising,

while FIFA’s expenses on development and committees and congresses have

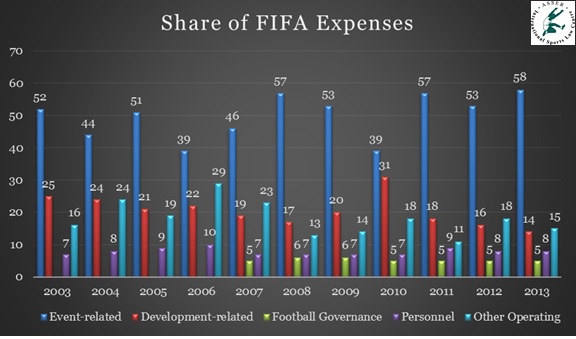

remained more or less stable. Graph 3 confirms that the evolution of FIFA’s

expenses is not linear, but general lessons can be drawn. The event-related

expenses have been representing more than 50% of FIFA’s expenses for 4 years

out of the last 5 (2010 stands out as an outlier). The trend towards the

reduction of the share of FIFA’s development expenses is clearly observable

(from 25% of total expenses in 2003 to 15% in 2013). This trend was only

reversed in the particular context of the South-Africa World-Cup in 2010. Besides that, the share of expenses linked to

wages and personnel has remained fairly stable (from 7% in 2003 to 8% in 2013).

Finally, the share of the other operating costs is difficult to compare across

the years, as FIFA has changed its accountancy system. Nonetheless, one can

assume that from 2007 onwards, other operating expenses and Football governance

(Legal costs and Committees and Congress expenses) expenses should be read together to match the

previous understanding of the notion of operating expenses. Thus, read

together, operating expenses would have risen from a 16% share in 2003 to a 20%

one in 2013.

Graph 2: FIFA Expenses

(per stream) in USD million (adjusted for inflation) 2003-2013

Graph 3: Share FIFA expenses over 2003-20013

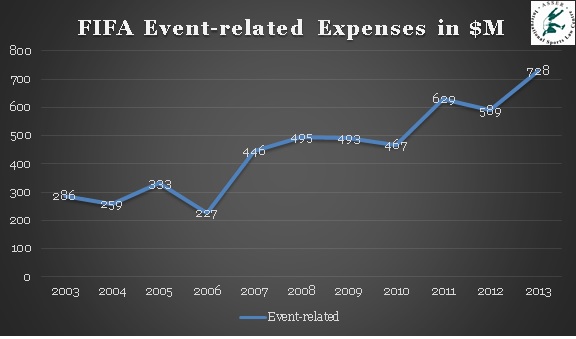

FIFA’s expenses are concentrated on the organization of its events (see

Graph 4). In 2013, 58% of the expenses incurred by FIFA were event related

(Graph 3). Indeed, since 2003 FIFA’s expenses on its events have increased from

USD 286 million in 2003 to USD 728 million in 2013. However, it is very

difficult to extract from the reports provided by FIFA the precise objects of

these expenses. It should be noted that the organizing country is

tasked with the financing of the main infrastructural investments (stadium,

transportation etc…), leaving little infrastructural costs bearing on FIFA. The

event-related expenses can be traced back to the financing of the local FIFA

World Cup Organizing Committee (the Brazilian committee received up to USD

221.6 million), prize money, travel and accommodation costs of the FIFA

officials and the participating teams and other expenses. Furthermore, they

also include the FIFA Club Protection programme that compensates clubs in

case of injuries suffered by players while on duty with their national teams.

Graph 4: FIFA

Event-related Expenses in USD million (adjusted for inflation), 2003-2013

FIFA is often keen on trumpeting its development-related investments. It

is even a key argument to justify its public utility: FIFA is to favour the development of football worldwide. This myth falls partially apart when one

looks at the numbers and at their recent trajectory. Indeed, as shown in Graph

5, since 2003 (omitting the exceptional South-African peak of 2010) the

Development-related expenses of FIFA have remained fairly stable (139 USD

million in 2003, 185 USD million in 2013), in spite of the tremendous growth of

both its overall revenues and expenses. Thus highlighting that FIFA has not

been very keen on developing redistribution streams in favour of its members, the players or the supporters.

Furthermore, the development schemes of FIFA are notoriously lacking

transparency and their ability to achieve any real trickle-down effect is not

warranted. The recent corruption scandals surrounding former FIFA

vice-president Jack Warner, have highlighted the risks of this development aid

getting lost in the pockets of corrupted local football officials. If FIFA is serious

about football development, and not only interested in PR, it should overhaul

its development funding scheme, both in terms of absolute numbers and of its institutional

set-up.

Graph 5: FIFA Development

related expenses in USD million (Adjusted to inflation) 2003-2013

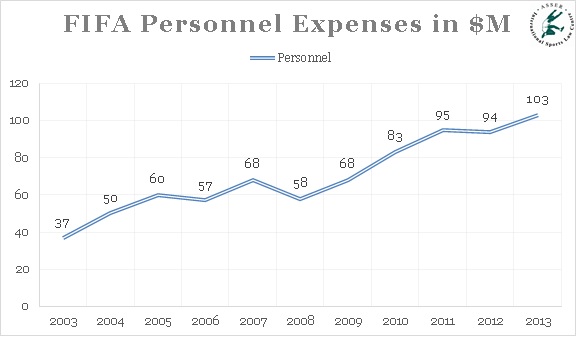

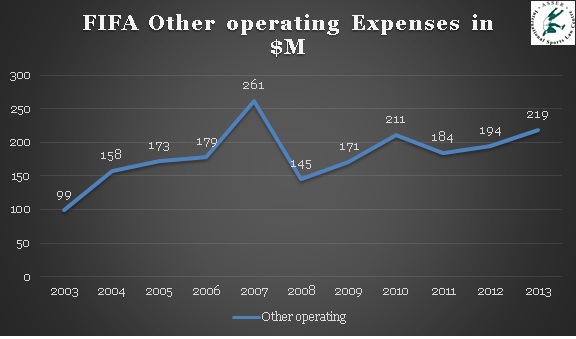

On the other hand, FIFA’s own personnel costs have grown over the last

10 years (Graph 6) from 37 USD million in 2003, to 103 USD million in 2013.

FIFA employs 400 staff members at its administrative centre in Zurich. The

administration of FIFA is a costly enterprise. In 2013 the operating expenses

reached 219 USD million (Graph 8), this includes the personnel expenses (Graph

6), but not the football governance expenses (the Committees and Congress expenses

in Graph7 and legal expenses), overall the operating cost reaches 276 USD

million! Those costs, especially the one dubbed other operating costs (Graph8)

are relatively obscure. What do they include? Personnel (102 USD million in

2013), information technology, buildings and maintenance (22 USD million in

2013), taxes and duties (17 USD million in 2013), depreciation and amortization

(12 USD million in 2013), communications (31 USD million in 2013) and other non determined expenses (32 USD million in 2013); but without

providing any more details about the concrete content of those categories. This

lack of explanation can only play in the hand of those that dismiss FIFA

altogether as an organization interested solely in its own wealth and well-being. One is

left puzzled by the amount of the operating costs, which are neither disbursed

for the organization of specific events (those are the event-related expenses

in Graph 4), nor for the organization of important meetings (those are the Congress

and Committees expenses in Graph 7). It may be that the FIFA building’s toilet are

made of gold or that its canteen is a three-star Michelin restaurant, but if so

we would like to know.

Graph 6: FIFA

Personnel Expenses in USD million (Adjusted to inflation) 2003-2013

Graph 7: FIFA

Committees and Congress Expenses in USD million (Adjusted to Inflation)

2003-2013

Graph 8: FIFA Other

Operating Expenses in USD million (Adjusted to inflation)

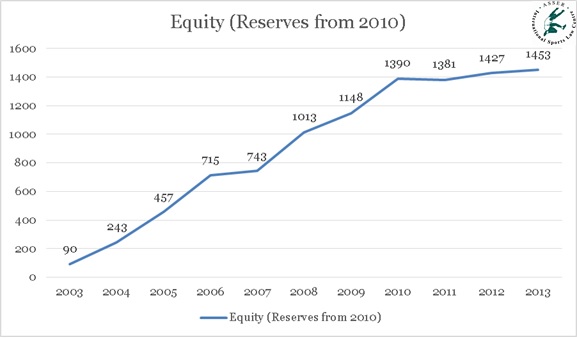

Finally, FIFA has constituted a richly dotted war chest. Over the last

10 years of economic success it has amassed huge financial reserves (Graph 9),

reaching up to 1453 USD million in 2013. Money lying still at a Swiss bank instead

of being invested in the development of football. This money is making money

for FIFA through the interests it produces. However, one can wonder why FIFA

would need to hold onto such a mountain of cash, instead of redistributing in

(in one way or another) to the ‘football family’. This perceived need is

illustrative of the transformation of FIFA into a proper business, far remote

from the interests of football and its actors.

Graph 9: FIFA reserves

in USD million (Adjusted to inflation)

Conclusion: Follow the money…

We have tried to follow FIFA’s money, in order to better understand if

some of the criticisms raised against the management of FIFA were justified.

From a macro point of view one fact needs to be highlighted: FIFA has been

making a lot more money over the last 10 years and very few of this additional

money has been redistributed via its football development schemes. In fact, it

is the only stream of outgoings that has seen its share in FIFA’s overall

expenses drastically cut from 25% to 15% over the last 10 years. FIFA should

take its development programmes seriously if it is to continue relying on them

to argue its good faith and willingness to contribute to global welfare.

Moreover, one characteristics of FIFA’s financial report is the lack of

transparency and readability of the data. One is challenged to figure out what certain

categories concretely mean. FIFA is spending a lot for things that cannot be

traced easily. At a micro-level, there is an urgent need for external observers

to be able to go through the detailed account of FIFA. One of the trigger for

rumoured, but also probably for real, instances of corruption lies in the fact

that the supervisory mechanisms provided by public scrutiny (through the press

and other institutions) is rendered moot by the accounting walls built by FIFA

to isolate its spending from the public’s eye.

Eventually, FIFA must let us (and help us to) follow its money. This would

be a giant step towards countering the corruption allegations being made and

also legitimating the role of FIFA as the governing institution of world

football. If the ‘football family’ is able to see and control the path followed

by FIFA’s money, the trust in FIFA as an institution will most likely improve.