Ever since UEFA started imposing disciplinary

measures to football clubs for not complying with Financial Fair Play’s break-even requirement in 2014, it remained a mystery how UEFA’s

disciplinary bodies were enforcing the Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play (“FFP”)

regulations, what measures it was imposing, and what the justifications were for

the imposition of these measures. For over a year, the general public could

only take note of the 23 settlement agreements between Europe’s footballing

body and the clubs. The evidential obstacle for a proper analysis was that the

actual settlements remained confidential, as was stressed in several of our

previous Blogs.[1]

The information provided by the press releases lacked the necessary information

to answer the abovementioned questions.

On 24 April 2015, the UEFA Club Financial

Control Body lifted part of the veil by referring FC

Dynamo Moscow to the Adjudicatory Body. Finally, the Adjudicatory Body had the

opportunity to decide on a “FFP case. The anxiously-awaited Decision was reached by

the Adjudicatory Chamber on 19 June and published not long after. Now that the

Decision has been made public, a new stage of the debate regarding UEFA’s FFP

policy can start.

This blog will firstly outline the facts of

the FC Dynamo case and describe how

and to what extent FC Dynamo breached the FFP rules. Secondly, the argumentation

and the disciplinary measures imposed by the Adjudicatory Chamber will be

scrutinized and compared to the measures imposed on other football clubs who,

unlike FC Dynamo, were capable of reaching a settlement with UEFA.

The build-up to the Decision

After the CFCB Investigatory Chamber met to

assess FC Dynamo’s monitoring documentation in August 2014, it quickly became

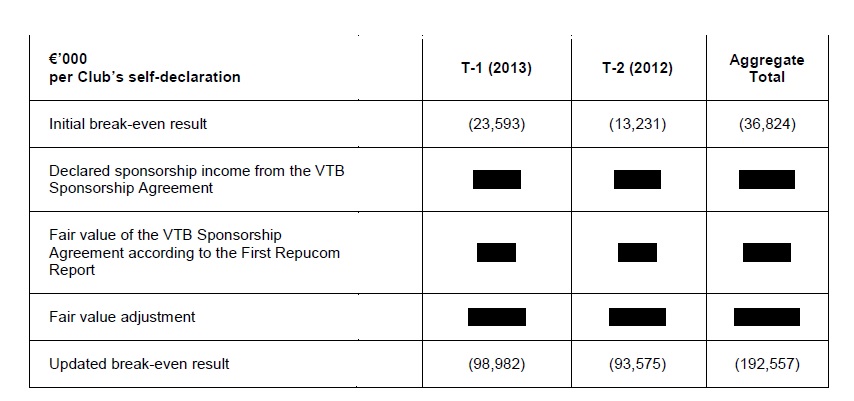

apparent that FC Dynamo had a break-even deficit. The deficit amounted to

€13,231,000 for 2012 and €23,593,000 for 2013, giving an aggregate total of

€36,824,000.[2] What

was more important for the assessment, however, was the close relationship the

Russian football club had (and still has) with JSC VTB Bank (“VTB”). VTB is

both the main shareholder in FC Dynamo (holding 74% of the shares in the club)

and the club’s principal sponsor.[3]

In accordance with Article 58(1) of the FFP regulations, the relevant income under

the regulations includes the revenue derived from sponsorship and advertising.

Furthermore, as is stipulated in paragraph 4 of that same Article, relevant

income from related parties (such as sponsors) must be adjusted to reflect the

fair value of any such transactions. Thus, the CFCB Chief Investigator requested

a copy of the sponsorship agreement between FC Dynamo and VTB in order to assess

whether it was in conformity with the “fair value” requirement.[4]

The documentation that FC Dynamo provided was based on a separate valuation

report by the firm ‘Repucom’.

The results of the calculations made by the

Investigatory Chamber are staggering. Where the break-even deficit without

taking into account the sponsorship agreement amounted to €36,824,000 for 2012

and 2013, the final number, after “fair value” adjustment of the sponsorship

agreement, amounts to a whopping €192,557,000. These results are shown in the

following table, which is taken from the Decision.

Table 1[5]

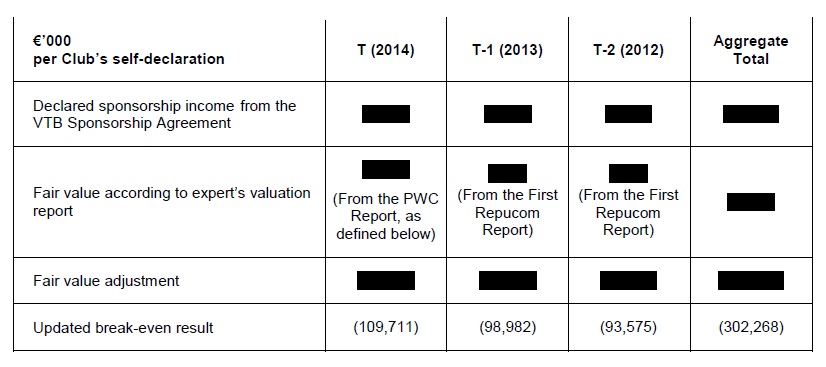

Given that the investigations of the

Investigatory Chamber were taking place towards the end of the monitoring

period 2014, the Chamber asked the Russian football federation to send updated

monitoring information covering the year 2014.[6]

In order to calculate the updated break-even result, it included a second

valuation report done by PWC, in addition to the Repucom report. The final break-even

result for the monitoring years 2012-2014 is €302,268,000, as can be seen in

the second table below.

Table 2[7]

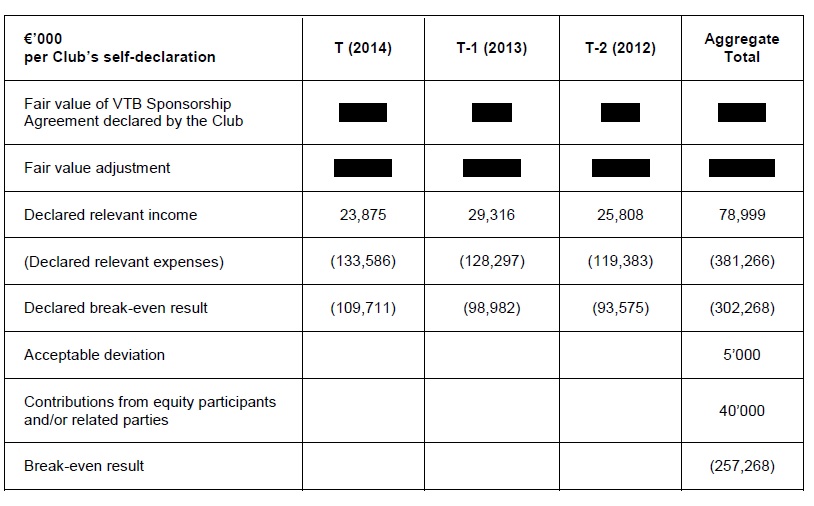

In

accordance with Article 61 (2) of the FFP Regulations, the acceptable deviation

from the break-even requirement is €45,000,000 for the monitoring period

assessed in the seasons 2013/14 and 2014/15. Therefore, in order to determine

the aggregate total of FC Dynamo’s break-even deficit is €302,268,000 -

€45,000,000 = €257,268,000 (see table 3).

Table 3[8]

Table 3[8]

An

aggregate break-even deficit of €257,268,000 is incredibly high. Especially if

one takes into account that the break-even deficit for the years 2012 and 2013

without the sponsorship agreement amounted to “only” €36,824,000. Even though

both the fair value of the VTB sponsorship agreement declared by FC Dynamo and

the fair value adjustment according to the Investigatory Chamber have been censored[9]

in the Decision, one can safely assume that the adjusted value of the

sponsorship agreement was roughly €200,000,000 less than what FC Dynamo was

receiving from VTB over a period of three years.

In

March 2015, the Chief Investigator informed FC Dynamo that UEFA would withold

the revenue obtained by the club in European competition.[10]

Not long after this decision, on 27 March a meeting was held between the

Investigatory Chamber and FC Dynamo. Though the details of the meeting remain

unknown, evidently no settlement between the club and the Investigatory Chamber

was reached, thereby making FC Dynamo the

first club failing to do so. As a consequence of the parties’ failure of

reaching a settlement agreement, the Chief Investigator referred the case to

the Adjudicatory Chamber. Moreover, in addition to the referal of the case in

accordance with Article 14(1) of the Procedural

Rules governing the UEFA Financial Control Body to the Adjudicatory

Chamber, the Chief Investigator suggested that FC Dynamo were to be excluded

from at least one UEFA club competition for which FC Dynamo would qualify in

the future, and advocated a fine of at least €1,000,000.[11]

Pursuant

to Articles 20(1) and 23(1) of the Procedural rules, the Adjudicatory Chamber

asked FC Dynamo to submit its observations and convened an oral hearing with

the club on 16 June 2015.[12]

Having received all the information it required, the Adjudicatory Chamber

proceeded to formulate its final Decision in accordance with Article 27 of the

Procedural Rules.[13]

The Adjudicatory Chamber’s

Decision

The Adjudicatory Chamber agreed with the

Investigatory Chamber that the key issue in the FC Dynamo case is the valuation of the sponsorship agreement with

VTB. The Chamber accepted that this value had to be adjusted to a fair value

and that the Expert Reports (Repucom and PWC) were an appropriate basis to do

so.[14]

Mostly, the Chamber based its final decision on the Investigatory Chamber’s

findings. In the end, it concluded that, “no matter which Expert Report

valuations are used, the Club has failed to fulfil the break-even requirement

because it had an aggregate break-even deficit within the range set out in Paragraph

58” of the FFP Regulations.[15]

FC Dynamo was granted the opportunity to

explain and justify why it had failed to meet the break-even requirement. The

club’s arguments can be summarized as follows:

1. The Russian

television market generates less revenues than the television market in other

European States, thereby creating an economic disadvantage for the Russian

clubs.[16]

2. The

Russian league imposes restrictions on foreign players.[17]

3. The

Russian clubs have suffered economically from the fluctuating exchange rates.[18]

The Adjudicatory Chamber counter argued as

follows:

1. Other European States

also generate less revenue from television. However, their clubs comply with

FFP rules.[19]

2. A vast majority of

European leagues are subject to limitations regarding the use of foreign

players. Russia is not “special” in that regard.[20]

3. Changes in exchange

rates may have had an adverse impact on FC Dynamo’s liability under a loan

denominated in Euros. However, this did not result in an adverse impact on the

Club’s break-even result. Furthermore, it must be remembered that the impact of

such fluctuations can be reasonably considered negligible in the context of FC

Dynamo’s overwhelming failure to comply with the break-even Requirement.[21]

FC Dynamo’s financial

projections and the Compliance Plan

In the observations submitted by FC Dynamo to

the Adjudicatory Chamber, the club also presented plans that will allow it to

fulfil the break-even requirement in the future. First of all, FC Dynamo’s

plans for a new stadium will allow it to generate more revenue.[22]

Secondly, the club indicated that it was seeking new investment in the club by

means of selling shares and that it will enjoy increased revenues from new

sponsorship and retail opportunities. [23]

In addition to the financial projections, FC Dynamo also held that it had

introduced new internal guidelines to govern its transfer activities (including

a salary cap) and has suggested that an emphasis will be placed on more youth

players being promoted to the first team.[24]

Again the Chamber was not convinced. FC Dynamo’s

proposals were deemed “vague in substance and its projections appear overly

optimistic. Whilst the Club’s good faith throughout the proceedings and

acknowledgement that it must adjust its business model is welcomed, its

proposed route to compliance with the Break-even Requirement is far from

certain.”[25] As

regards the stadium, since it will not be owned by FC Dynamo itself[26],

the Chamber argued that it remains unclear whether it will generate more

revenue. And even if it does, this will not happen before 2018. It also remains

uncertain whether FC Dynamo will attract new investment. The Chamber is aware

of VTB’s plans to sell its shares, but is uncertain if any sale can be effected

in the near future. The potential buyer of these shares, Dynamo Sports Society,

and VTB have only signed a non-committal intention clause regarding the

transfer.[27]

Further, the Chamber deems it unlikely that FC Dynamo will comply with the

break-even requirement through increased sponsorship revenue. As FC Dynamo

itself pointed out in its observations, “unfavourable economic conditions” may

make it difficult to attract new investment.[28]

More importantly, “having regard to the scale of the Club’s failure to fulfil

the Break-even Requirement, even a strong increase in revenues from commercial

activities and player sales would be unlikely to bring about FC Dynamo’s

sustained and consistent compliance with the Break-even Requirement, for so

long as the related party issues surrounding VTB’s involvement with the Club

persist”.[29]

Lastly, the Chamber welcomes the club’s ambition to reform its transfer

activities and place more emphasis on youth players, but similarly held that

there is no guarantee that FC Dynamo will actually comply with such policies.[30]

Disciplinary Measures

According to the Chamber, FC Dynamo failed to justify

the break-even deficit convincingly and, consequently, faced disciplinary

measures. By form of reminder, the Chamber stressed that the objectives of the

FFP Regulations included the encouragement of clubs to operate on the basis of

their own revenues and, thus, the protection of the long-term viability and sustainability

of European football. Furthermore, the principle that all clubs competing in

UEFA’s club competitions must be treated equally underpins the Regulations. Since

not meeting the break-even requirement may directly affect the competitive

position of a club, to the detriment of clubs who comply with the FFP

Regulations, this principle has even greater force.[31]

The main, and extreme, disciplinary measure

imposed by the Chamber upon FC Dynamo, consists of an exclusion from the next

UEFA club competition for which the club would otherwise qualify in the next

four seasons (i.e. the 2015/16, 2016/17, 2017/18 and 2018/19 seasons). Given the scale of the club’s failure to

comply with the break-even requirement, the measure is regarded by the Chamber

as the “only appropriate measure to deal with the circumstances of this case”.[32]

As for FC Dynamo, under Article 34(2) of the Procedural Rules, it had 10 days

to appeal the Decision in writing in front of the CAS.

Concluding remarks

First and foremost, the exclusion from

European competitions as a disciplinary measure has, so far, only been imposed on

FC Dynamo. None of the club with whom the Investigatory Chamber had reached

settlement agreements have been excluded from European competitions for

breaching the break-even requirement.[33]

The Adjudicatory Chamber had stated numerous times in its Decision that the key

factor in the FC Dynamo’s case was

the scale of the club’s failure to comply with the break-even requirement. From

an objective point of view, a break-even deficit of €257,268,000 is very high

indeed. In the view of the Chamber, it justified such a far going disciplinary

measure. The question remains, however, what the break-even deficit was for

those clubs who managed to reach settlement agreements. Was the break-even

deficit for clubs like Manchester City and PSG lower or higher than 257

million? If it was equal or higher than this amount, how did these clubs manage

to settle where FC Dynamo failed? Would the measures imposed on FC Dynamo be

considered proportionate if other clubs had the same or higher break-even

deficit?

On a different note, the FC Dynamo case does allow us to understand better the rationale

behind the Adjudicatory Chamber’s decision to impose certain disciplinary

measures. It is interesting to see how much weight it places on sponsorship

agreements that, according to the Chamber, do not represent a fair market

value. This is not only useful information for football clubs, but also to

third parties who might be interested in sponsoring a football club. On a

downside, we will probably never know exactly what the value of the sponsorship

agreement was according to the club, and how it was adjusted by the two

Chambers. Even though FC Dynamo had the right to keep certain information

confidential, knowing the two figures would have helped us to better understand

the reasoning used by the Chambers in reaching their decisions and choosing to

exclude FC Dynamo from UEFA competitions.

Finally, these are still crucial times as

regards the functioning and the legality of UEFA’s FFP rules. The rules are

being challenged in front of both the French and Belgium courts as we speak and

there is always the possibility (though remote, see our blog) of the

European Courts having to judge on the matter. A challenge in front of the CAS could

be seen as a welcome contribution to test the legality, the functioning and the

proportionality of the rules. Though it is currently unknown whether FC Dynamo

has made use of the opportunity to appeal the case to the CAS.

[1] See e.g.: Luis Torres, “Financial Fair Play:

Lessons from the 2014 and 2015 settlement practice of UEFA” (8 June 2015); and Oskar van

Maren, “The Nine FFP Settlement Agreements: UEFA did not go the full nine yards” (19 May 2014).

[2] Decision in Case AC-02/2015

CJSC Football Club Dynamo Moscow of 19 June 2015, para. 5.

[3] Ibid, para. 56.

[4] Ibid, paras. 7-10.

[5] Ibid, para. 11.

[6] Ibid, para. 8.

[7] Ibid, para. 15.

[8] Ibid, para.

24.

[9] Under Article 33(3) of the

Procedural Rules Governing the UEFA Financial Control Body, “the adjudicatory

chamber may, following a reasoned request from the defendant made within two

days from the date of communication of the decision, redact the decision to

protect confidential information or personal data”.

[10] Decision in Case AC-02/2015,

para. 17.

[11] Ibid, para.

25.

[12] Ibid, paras.

28-31.

[13] Under Article 27 of the

Procedural Rules, the adjudicatory chamber may take the following final

decisions:

a)

to dismiss the case; or

b)

to accept or reject the club’s admission to the UEFA club competition in

question; or

c)

to impose disciplinary measures in accordance with the present rules; or

d)

to uphold, reject, or modify a decision of the CFCB chief investigator.

[14] Decision in Case AC-02/2015,

para. 56.

[15] Ibid, para. 60.

[16] Ibid, para. 67.

[17] Ibid, para. 70.

[18] Ibid, para. 72.

[19] Ibid, paras. 68 and 69.

[20] Ibid, para. 71.

[21] Ibid, paras. 73-75.

[22] Ibid, para. 84.

[23] Ibid, paras. 89 and 94

[24] Ibid, para. 97.

[25] Ibid, para. 83.

[26] According to para. 85, the

stadium will be owned and operated by a separate legal entity named ‘Assets

Management Company Dynamo’.

[27] Ibid, paras. 89-90

[28] Ibid, para. 91.

[29] Ibid, para. 96.

[30] Ibid, para. 97.

[31] Ibid, paras. 77-80

[32] Ibid, paras. 101-102

[33] For more information on the

settlements agreements, see our blog from 9 June 2015.