[Upcoming publication] Janne E. Nijman: ‘Bertha von Suttner: Locating international law in novel and salon’

Published 8 March 2022

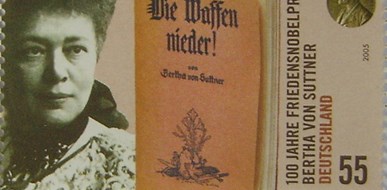

Bertha von Suttner, the best-selling author of the anti-war novel Die Waffen Nieder! stood at the foundations of The Hague’s international legal institutions and was the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. For this year’s International Women’s day, we highlight Janne E. Nijman’s exploration of diaries, articles and a novel to portray this unorthodox international thinker in her upcoming article ‘Bertha von Suttner: Locating international law in novel and salon’.

Her face featured on banknotes, and on stamps in Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. You will still find her name on many city streets across Europe and her quotes on peace on social media. And when you enter the Peace Palace in The Hague, you will come across the copper face and chest of the ‘the spiritual mother of the Peace Palace’, who witnessed the work on the Peace Palace foundations as one of the guests of honour.

The Austrian feminist and peace activist Baroness Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914) was an unorthodox and colourful person and a woman far ahead of her time. A contemporary of Tobias Asser (1838-1913), the legal scholar after whom the Asser Institute is named, Von Suttner and Asser - each in their own way - worked tirelessly to establish the Hague Conferences in 1899 and 1907. They would both receive the Nobel Peace Prize for their help in developing an international order aimed at peace rather than based on war.

‘A woman who imagined, argued, and contributed to the development of international law and institutions.’

Largely ignored

However, as with many other women in the history of international (legal) thought, Von Suttner and her thinking on international law have been largely ignored in international legal history, writes Nijman, ‘as not fitting traditional understandings ‘of what counts as international thought and […] of who counts as an international thinker.’

To include Suttner and her work in international legal history, Nijman moved beyond the ‘gendered frame of international legal history’, and studied sources that are often not considered relevant to international law or legal history. That is: female diaries, magazine articles, and the bestselling novel Die Waffen Nieder! (1889). In her article, Nijman locates international law in Von Suttner’s writing and actions, portraying ‘a woman who imagined, argued, and contributed to the development of international law and institutions.’

Horrors of war

In 1889, when she was 46, Von Suttner published ‘Lay down your Arms!’ (‘Die Waffen nieder!’), an anti-war novel that would propel her to world-fame. To depict the horrors of war, Von Suttner chose to write a novel rather than a nonfiction work, because she realised that novels would reach a wider audience. Her strategy worked. Die Waffen nieder! would be published in 37 editions and translated into 15 languages, catapulting Von Suttner to become a leading figure in the emerging international peace movement. According to Nijman, the book shows that Von Suttner held a ‘rather well-developed - and at times fairly sceptical - outlook on international law.’

In Die Waffen Nieder!, Bertha von Suttner describes the horrors of war from the perspective of a suffering woman, Martha (Bertha’s alter ego). As Nijman writes: “Die Waffen Nieder! is a first-person novel that tells the life-story of Martha von Tilling amid four European wars - 1859, 1864, 1866 and 1870/71. It describes in very realistic terms the suffering war brings to both men and women. While this largely explains its world fame, it is also a novel of international (law) ideas. Martha examines contemporary international law issues such as the problem of secret treaties, the right to self-determination of the people of Schleswig-Holstein, ‘historic rights’ claimed by Denmark as a ‘right cause’, or other causa belli claimed by European states to justify war. She passionately attacks the conservative perspectives on state, war and international order so all-pervasive in the German-language world (…).”

Harsh critic

Von Suttner, who, together with her partner Arthur Von Suttner, worked as a journalist and teacher, had witnessed the effects of war. Nijman: ‘During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, Arthur reported on the war for the leading newspaper of the establishment, the Neue Freie Press. Next to her journalistic and feuilleton writing, Bertha transformed their home into a hospital for wounded Russian soldiers.’ Von Suttner was a harsh critic of the old social and political order of fin-de-siecle Vienna and the disintegrating Austro-Hungarian Empire. She advocated social justice and a transformation of the old international order: ‘Gestern: Gewalt als Recht. Morgen: Recht als Gewalt’. She argued that pacifism and solving disputes by talking rather than by use of force, was possible. For protagonist Martha, war is the negation of ‘civilisation’ and she derided the sense of superiority of European ‘civilised nations’. Nijman: “She mocks the ‘barbarism’ of self-acclaimed ‘civilised nations’ and calls for ‘the triumph of the intellect’ over the irrationality of war. Through her eyes the reader learns how society maintains this ‘savagery’ (…): by social conventions that define a woman’s role by her (breeding) function to the military, by a culture of patriotism and militarism, and by a Roman Catholic clergy who treats warfare as a product of the will of God.”

‘War dehumanises’

In her article, Nijman sketches how protagonist Martha and her husband Frederick argue for a peaceful order based on international law, a field Von Suttner was interested in but critical of. Nijman: “In Martha’s red diaries, she copies excerpts of international legal documents of her time. In a blue cahier, Frederick and Martha develop their ‘peace through law’ argument by engagement with peace studies’ authors from Aristophanes to Kant. In the international legal order, they advocate, war is not a natural disaster but inflicted by human choice, it is ‘a crime’ or ‘Völkermord’ as Martha phrased it at the graveyards of Königgrätz (1866). War does not morally improve humanity, it ‘dehumanises’.”

According to Nijman, Von Suttner was more radical than her contemporaries who argued for the development of international humanitarian law. Von Suttner attacked the international right to go to war and argued for the abolition of standing armies - as nations with armies would become armed nations. Protesting against the arms race and the industrialisation of weaponry, protagonist Martha presciently calls for a confederation or ‘union’ of states, a ‘league of peace’ in Europe, and calls for the peaceful settlement of international disputes by an international ‘court of law’. At the end of the novel, Martha explicates the agenda of the peace movement and pleads one last time: ‘to move the Governments to submit their differences in future to an Arbitration Court, appointed by themselves, and so once for all to enthrone justice in place of brute force.’

Salon diplomacy

The success of Die Waffen Nieder! propelled Von Suttner to world-fame. She used her influence to found peace societies in Austria and Germany, and travelled Europe as an activist for peace and social justice. With her high standing as a world-leading peace activist, Von Suttner would become ‘the only woman permitted’ at the opening ceremony of the 1899 (Hague) conference at Dutch Queen Wilhelmine’s Huis ten Bosch'.

Not allowed access to the formal sessions of the 1899 Hague conference, Von Suttner instead used her position to contribute to the peace through law project, writes Nijman through ‘a typical female practice to influence intellectual and political debates’: salon diplomacy.

The salon, a conversational gathering in an intimate setting, was an important social institution in the circles of Bertha and her alter ego Martha. From the seventeenth and eighteenth century in France onwards, and later elsewhere in Europe as well, aristocratic ladies would host salons that influenced the cultural and social changes of their times. Salonnières held power. Under their influence, political plots were hatched, new literary trends were started, scientific discoveries were publicised, and new ideas were launched.

Small cosmopolitan elite

In her article, Nijman recounts how Von Suttner took her agenda of arbitration, disarmament and the abolishment of the ius ad bellum to The Hague to work them through her salon in 1899 and 1907. As salonnière - first at the Grand Central Hotel in The Hague and later in the Kurhaus hotel at Scheveningen beach - Von Suttner created an informal social space for frank conversations among the small cosmopolitan elite of diplomats, journalists and international legal experts. There, people would meet and discuss the latest developments that were at issue in the formal sessions of the Peace Conference. Nijman: “Her salon was ‘always full of callers, and from early in the morning with interviewers’ for international newspapers. (…) As the most prominent woman of the international peace movement, she could as a salonnière lead authoritatively the exchange of progressive (legal) pacifist ideas in a private setting, thus contributing to the creation of an international public sphere avant-la-lettre. Journalists were not admitted to the [Conference] deliberations, but at her Salon they informed themselves, spoke with delegates and consulted international lawyers and peace activists. The latter in turn hoped to mobilise ‘public opinion’ through the press and to influence the representatives.”

‘Popularisation of international law’

Von Suttner was important for the development of international law, as she changed the minds and perceptions of people with her book, and through her relentless campaigning for peace. As Nijman writes: "Bertha von Suttner was not an international lawyer in the classical sense. Yet with her novel and other writings she did contribute to what Lassa Oppenheim in 1908 claimed to be one of the main tasks of the science of international law: ‘popularization of international law’. (…)"

Although Von Suttner would in her own way help lay the foundations of today’s international legal institutions, she would, throughout her life, remain ambivalent about international law. In 1912, she wrote to a friend about international lawyers: ‘Das sogenannte >Völkerrecht< - trockene Juristerei – past nicht in die Friedensbewegung, ungefähr wie das Rote Kreuz .‘ (‘The so-called >international law< - dry jurisprudence - does not fit into the peace movement, much like the Red Cross.') And, four weeks before her death: ‘Die Völkerrechtslehrer werden den Pazifismus erdrosseln.’ (‘The teachers of international law will strangle pacifism’).

As Nijman concludes: "In Suttner’s view, the development of the laws of war to ‘humanis[e] war’ had gummed up the works of the peace movement and driven ‘a wedge (…)’ into ‘the deliberations of the Peace Conference’. In her view, only a ban on war, disarmament, and the pacific settlement of international disputes by an international court of arbitration would do. She would fight for it until the end of her life".

A few days after her death, the First World War broke out.

Read the full paper at SSRN

Bertha Von Suttner: Locating International Law in Novel and Salon, by Janne E. Nijman, forthcoming in: Tallgren, I. (ed.), Portraits of Women in International Law: New Names and Forgotten Faces?, Oxford University Press.