International Women’s Day: Janne Nijman puts the spotlight on peace activist Bertha von Suttner (1843 - 1914)

Published 8 March 2019

Peace activist Bertha van Suttner had the guts to take on a male-dominated field.

Today there are many influential women working in international law. However, one needs a looking glass to find influential women in international legal history. To celebrate International Women’s Day, Prof Dr. Janne E. Nijman, academic director of T.M.C. Asser Instituut and professor of History and Theory of International Law at the UvA, puts the spotlight on a remarkable woman in the history of international law: the peace activist Bertha van Suttner (1843-1914). “She had the guts to take on a male-dominated field.” An interview.

Why is it important that we learn more about women in the history of international law?

“Gender inequality contributes to conflict around the world. Sustainable peace can only be reached when the gender imbalance is addressed. I find it problematic that, although women represent half of the world’s population - and therefore half of its potential - women’s history is largely underrepresented in international legal history. By focusing on the male side of history, we are neglecting the role women played in history. This still has an impact on today’s society. Our culture, our power structures and our power codes are still male-oriented. Unless we change these, and change the way we think about power and authority, women will not fit in. Apart from gender equality being a fundamental human right, I believe gender equality is crucial to achieve peaceful societies, an issue that concerns men and women alike. As our common future has to be shaped by women and men, it is high time that we find female role models – in history, in international law and politics. We need to know and teach about women who dared to swim against the tide. Bertha Von Suttner did exactly so. She was the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize, so she is an important historical example.”

Can you tell us a bit about Bertha Von Suttner?

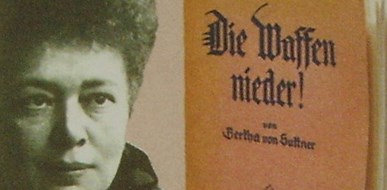

“Bertha von Suttner was a female comrade of Tobias Asser (1838-1913), the scholar after whom the Asser Institute is named. They lived in the same time, and they would both receive the Nobel Peace Prize for their help in developing an international order based on peace rather than war. In 1889, when she was 46, Von Suttner published ‘Lay down your Arms!’ (‘Die Waffen nieder!’), an anti-war novel that would make her world famous. In her book, she describes the horrors of war from the perspective of a suffering woman. She argues that pacifism and solving disputes by talking, rather than by use of force, was possible. To get this message across, Von Sutner chose to write a novel rather than a nonfiction work, because she believed that novels would reach a wider audience. Her strategy worked, Die Waffen nieder was published in 37 editions and translated into 15 languages, catapulting Von Suttner to become a leading figure in the emerging international peace movement.”

What was so special about this?

“It is hard to believe these days, but at the time Von Suttner published her book, pacifism, or the idea that you could solve international disputes by arbitration rather than war, was not a popular idea. States lived in an anarchical, violent world. War was taken for granted by most, considered a given. Von Suttner endlessly campaigned against this view, which she considered to stem from military interests. As she came from an aristocratic family and her own father - who died before she was born - worked in the military, Von Suttner went against the social code she was raised in. She said: ‘the military organization of our society has been founded upon a denial of the possibility of peace, a contempt for the value of human life, and an acceptance of the urge to kill.’ Von Suttner believed that this view, this acceptance of the status quo, was one the biggest problems of her time. She worked endlessly to promote the idea of legal order among states to prevail over violence between states. With her outspoken ideas about peace and human potential, she went against the establishment and against the view of many, as pacifism, rule of law, and peace between states, were considered to be ’utopian dreams’.”

Was Von Suttner a feminist avant-la-lettre?

“That, I am not sure of. Von Suttner broke through gender barriers by her work as a writer and activist. She was an outspoken leader in a society in which women were to be seen, not be heard. But she did not actively participate in the movements for women’s suffrage, for instance, which she explained due to a lack of time. She instead focused on reaching out to other women in the international peace movement, though she kept close contact to the women’s suffrage movement. As a sign of joint solidarity, for instance, Von Suttner was a prominent participant of the 1904 ‘International Women’s Conference’ (‘Internationale Frauen-Kongress’) in Berlin. Von Suttner knew, though, and this is what I appreciate about her, that conflict can only be avoided if both men and women together struggle for peace, which required an absolute belief in gender equality. ‘The tasks involved in mankind's continuing ennoblement are such that they can only be fulfilled through fair and equal cooperation between the sexes’, she wrote.”

Why was Von Suttner important for the development of international law?

“She contributed to the groundwork for today’s institutions, by changing the minds and perceptions of people with her book and her relentless campaigning for peace. Her other contributions were quite remarkable too and they speak of her vision. In 1891 she founded the ‘Austrian Society for Friends of Peace’ (‘Österreichische Gesellschaft der Friedensfreunde’) and the German equivalent a year later. In 1897 she presented Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria with a list of signatures, while she urged for the establishment of an International Court of Arbitration. That she has put her weight behind this idea has been crucial for the realisation of such an institution some years later.”

“She was also the only woman who participated in the Hague conferences of 1899 and 1907 - Tobias Asser being one of the male crowd. Von Suttner was actually highly critical of the second Hague conference in 1907, and warned of a war to come. When accepting her Nobel Peace prize, she said: ’(…) whether our Europe will become a showpiece of ruins and failure, or whether we can avoid this danger and so enter sooner the coming era of secure peace and law in which a civilisation of unimagined glory will develop. The many aspects of this question are what the second Hague Conference should be discussing rather than the proposed topics concerning the laws and practices of war at sea, the bombardment of ports, towns, and villages, the laying of mines, and so on. The contents of this agenda demonstrate that, although the supporters of the existing structure of society, which accepts war, come to a peace conference prepared to modify the nature of war, they are basically trying to keep the present system intact’”

“This point about structures is important. It tells us about how she approached the status quo, the structures that defined the international society. Her attitude that speaks from her words reminds me of the words of contemporary thinker, Alexander Wendt: ‘Anarchy is what states make of it’. In other words: anarchy and war are not coming to us as natural disasters like storms or floods but they are created by human choices. Von Suttner addressed the structures humans built and argued their contingency. That is a hopeful thought, change is possible!”

What can we learn from Bertha Von Suttner?

“What Von Suttner achieved with her quest for peace, is remarkable. Her courage to take on such powerful male-dominated field is admirable. She wrote at a time when women hardly participated in the fields of international relations, law, and diplomacy. I believe we should remember and take inspiration from Von Suttner’s stamina, her persistence and her eloquence. Her words and perspective are still highly valid. Von Suttner’s death in 1914, weeks before the outbreak of the First World War, was tragic, as she had warned of what would become such a devastating war for most of her life. In the last months of her life, while suffering from cancer, she helped organise a new Peace Conference, which had to take place September 1914. However, the conference never took place, as Von Suttner died on 21 June 1914. A few weeks later Franz Ferdinand was killed, triggering World War I. Her close friend Alfred Hermann Fried wrote an obituary, in which he mentioned von Suttner’s very last words: “Lay down your arms – tell it to many – many!” Here in The Hague, there is a bust of Bertha von Suttner in the hallway of the International Court of Justice that should remind international lawyers of her ideas. But let us take this year’s International Women’s Day as an opportunity to carry these ideas beyond the international legal community and make Bertha von Suttner an inspiration to all of us.”